The warm winds off the Propontis carried scents of sea salt and spring jasmine through the courtyards of the imperial villa in Nicomedia. Beyond the marble colonnades and ornate mosaics of purple porphyry and green serpentine stone, a hush lay over the chambers of the emperor. Soldiers in scarlet stood sentinel, unmoving. Courtiers had withdrawn. The golden eagle standard drooped in the hallway, casting a flickering shadow beneath the torches that burned low.

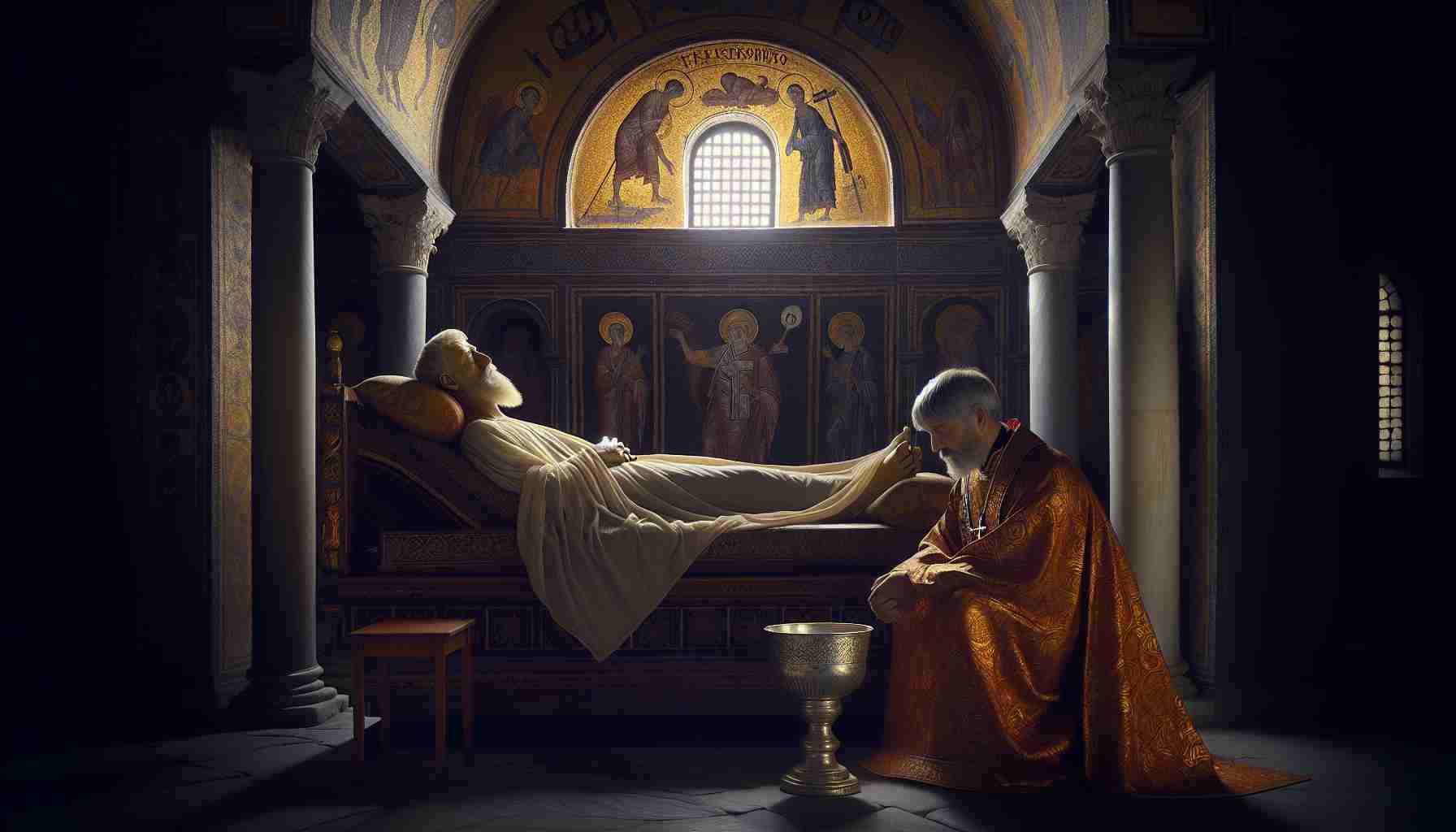

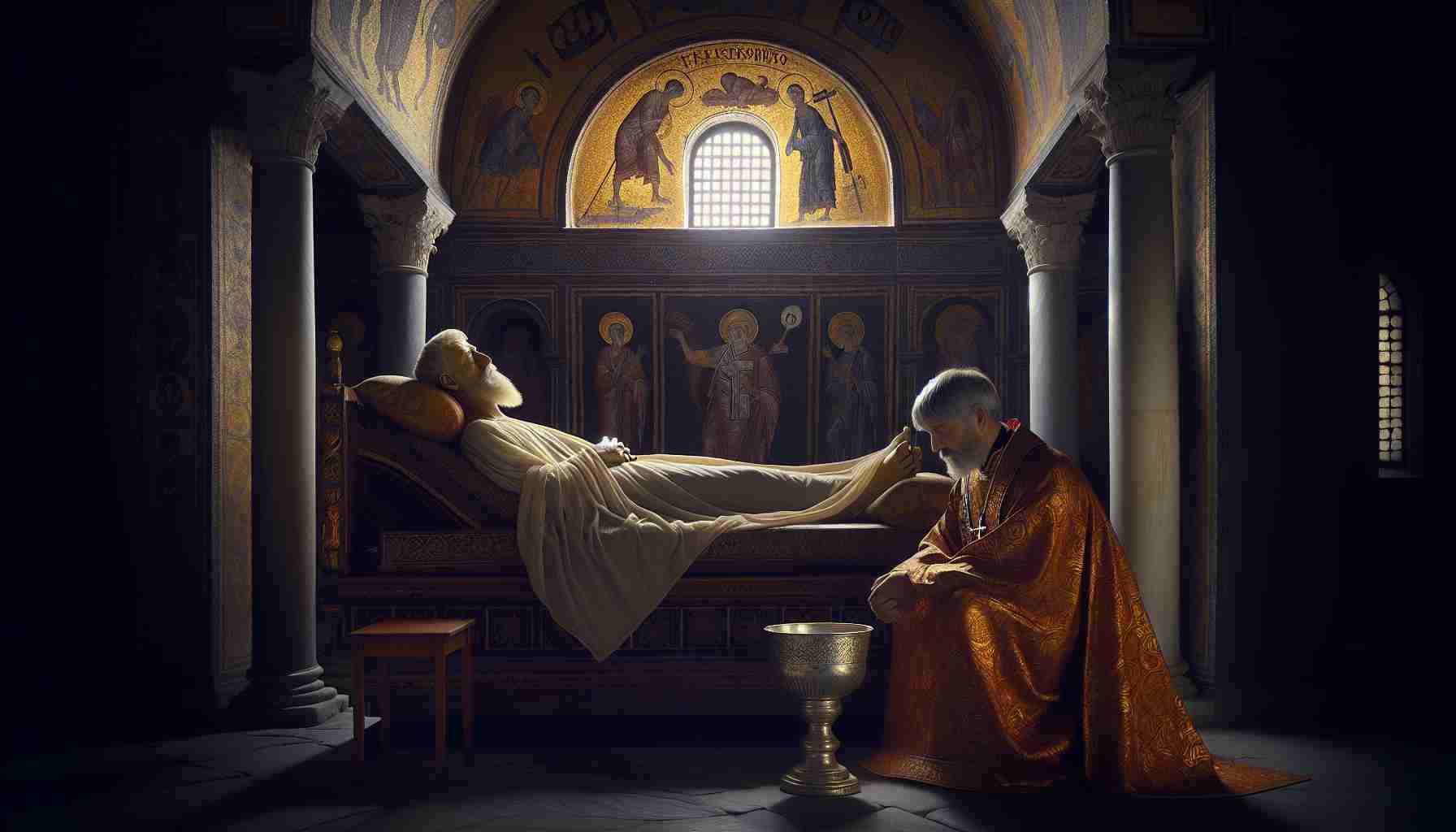

Inside, the once-mighty Constantine lay pale upon a cedar couch. His breath was shallow, the lines of battle, empire, and time etched deeply into his brow. Gone was the armor that had glittered beneath the sun at the Milvian Bridge. Here was a man unclothed of ambition, wrapped instead in simple linen—the garments of the dying.

At his side knelt Eusebius, bishop of Nicomedia, hands folded in prayer. A silver basin of water glimmered nearby.

Iron from Constantine’s voice had long faded, but in a whisper that defied weakness, he asked, “Is the hour come?”

The bishop nodded solemnly.

No throne lay beyond this moment. No senate to please. On May 22, 337 AD, Constantine the Great received holy baptism, a sinner’s surrender into grace. The waters poured over a brow once crowned with laurel. This man who sculpted empires now entered the kingdom not made by hands.

Outside, the city held its breath.

From the forum to the baths, from the basilicas adorned with images of Christ to the pagan temples he had no longer given state favor, Nicomedia braced to yield its emperor to eternity. The same man who had stood in battle under a Chi-Rho banner—claiming to conquer in the sign of Christ—had now knelt to that same Name.

Constantine’s faith was no unblemished relic. He had wielded religion like a sword and shield, discerning unity through decree, ordering bishops-councils with the same strategy he used to manage provinces. Flawed, too, was his temper; ruthless in moments, indulgent in others. But his vision—God had used it.

Back when the edict rang out from Milan’s palace halls in 313, the chains fell off the wrists of thousands. Christians could now breathe freely, build churches with soaring domes, sing psalms openly in the streets. The blood that had soaked arenas like those of Smyrna and Antioch lessened its tide. The cross was no longer a symbol of shame but of triumph.

Then came the City.

From the Bosphorus shore, rising like prophecy, grew Constantinople. A new Rome—where Christ reigned instead of Caesars as gods. He named it Nova Roma, but the people called it Constantine’s city. In the Hippodrome he raised an obelisk from Egypt; in Hagia Eirene, a church of Holy Peace, stone gave voice to theology. From this eastern throne, the faith would surge through the Balkans, over Scythian plains, down into Coptic deserts.

And in the halls of Nicaea, beneath cavernous arches, the Nicene Creed was born. Bishops debated divinity. “Begotten, not made,” they declared of the Son. That Christ was of the same essence as the Father—homoousios—poured like oil into the flame of orthodoxy. Constantine, not yet baptized, presided over the wordsmithing of eternity.

But even bishops contradict. Even empires fail.

Rumors whispered after his death: That he favored Arianism; that he waited for baptism so that all his sins—from political assassinations to wars of ambition—could be washed away at once. That he was Roman first, Christian second. Yet even these speculations revealed something greater: that God weaves through crooked lines.

In the Book of Acts it is written, “From one man he made all the nations... and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands” (Acts 17:26). Perhaps it was for this time—this deathbed moment—that Constantine was born.

The sun lowered beyond Nicomedia, washing the city in crimson.

His sons waited with silent, anxious eyes. They would quarrel. Civil war would howl again. Yet from Constantine’s body, now still in death, reverence rose. He was carried back to Constantinople in procession, robed in imperial purple, placed not beneath domes of Caesar but within the Church of the Holy Apostles. There, amidst lamps of gold and the bones of martyrs, he would be buried as “Equal to the Apostles.”

History bent beneath the weight of that title.

Stone would remember his contradictions. But believers would remember that Constantine, conqueror of Rome, had bowed to a greater Lord. The tomb of empire bore a cross above it now.

And in the singing choirs of Constantinople, as censers swung and echoes of Kyrie eleison filled the vaults, it was whispered and sung and believed: A Christian emperor had joined Christ today.