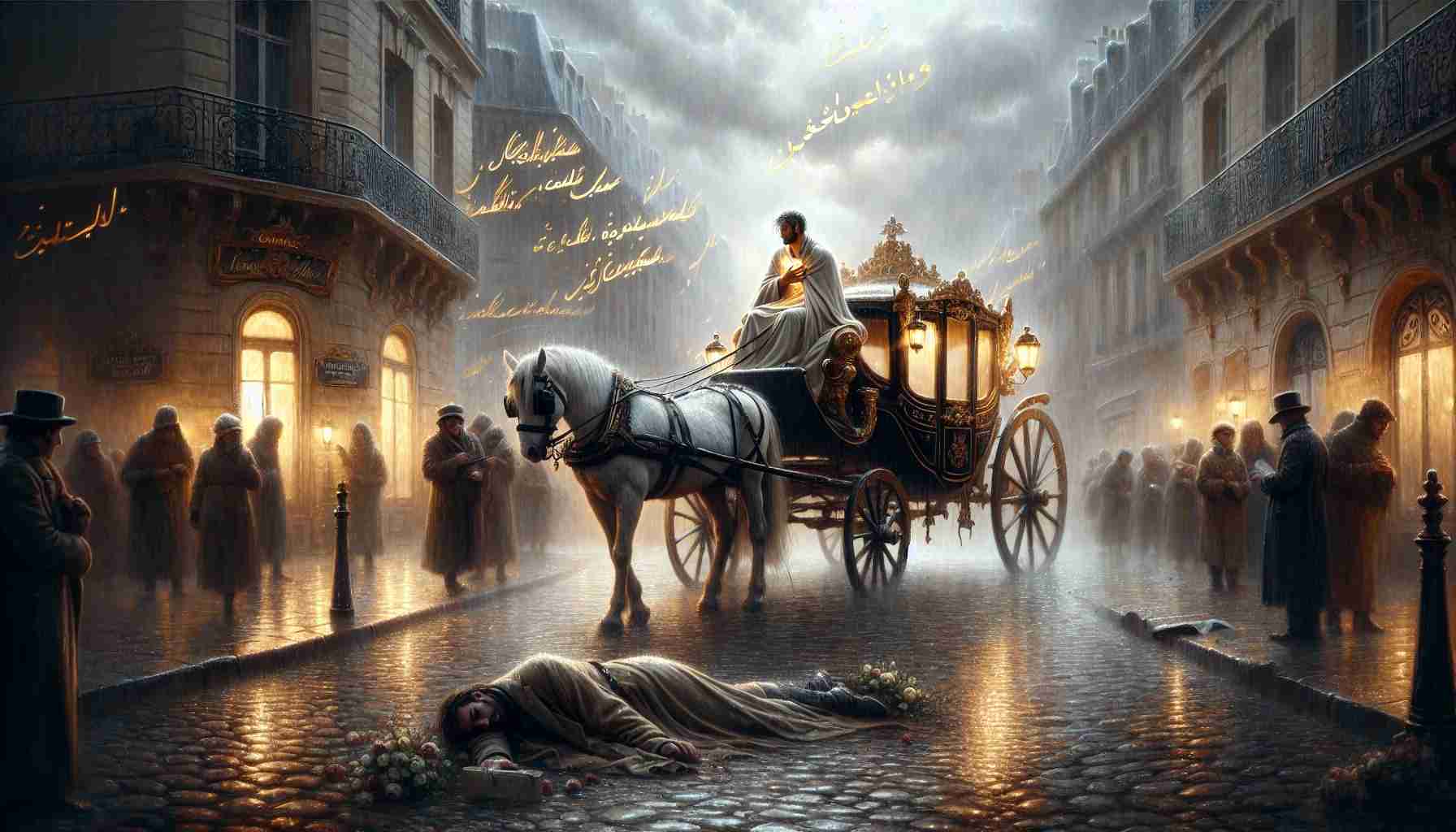

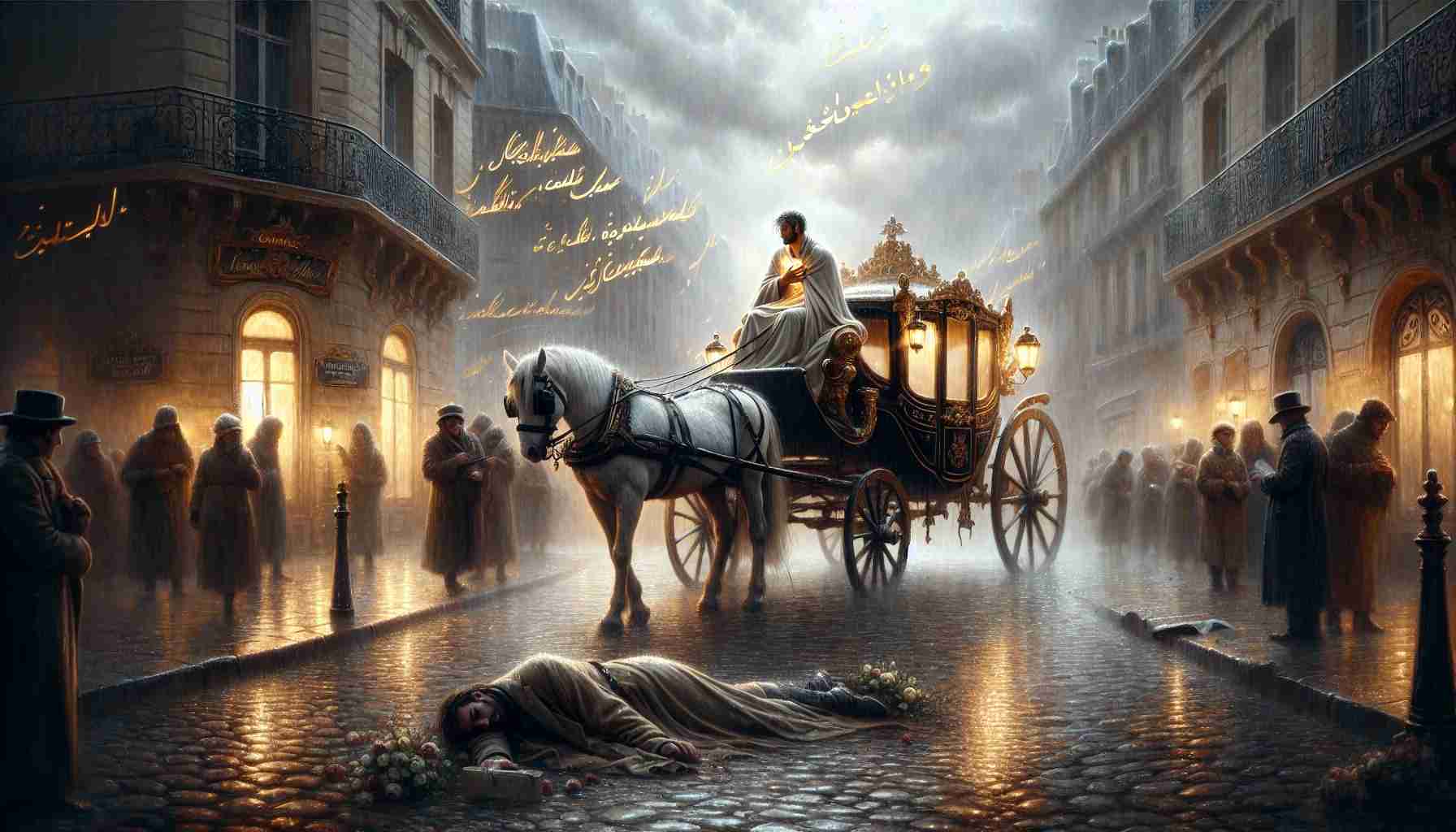

Rain glistened on the cobblestones of Paris, though the hour was past midday. The sky hung low, swollen with unspent sorrow, as the royal carriage rattled down the Rue de la Ferronnerie. Within, King Henry IV of France leaned back in his seat, fingers absentmindedly tracing the hilt of his sword. His mind was elsewhere—on Bordeaux, where grain wagons were delayed again, and on Béarn, where Calvinists whispered rumors of betrayal. Still, his shoulders eased with the knowledge that peace, however fragile, still reigned.

He had earned the name "Good King Henry," not through brutish conquest, but by steady hands that stitched a shattered kingdom back together. France had bled for thirty years—Catholics and Huguenots alike consumed by holy fury. Henry, once Protestant, had laid down his sword and taken up the cross, converting to Catholicism for the crown. "Paris is worth a mass," he had famously quipped. But the truth had been weightier than wit. With the Edict of Nantes, he dared promise tolerance. Protestants could worship, own land, and live without fear. It had not satisfied everyone, but it had stopped the killing.

On the street corner ahead, a figure pressed into the crowd. François Ravaillac, his tunic wet and coarse, murmured psalms into his beard. God had revealed to him how the king planned to wage war upon the Pope, or so Ravaillac believed. A zealot, not mad, convinced that peace with heretics was treason against heaven. In an inner pocket, the steel of his knife glinted. He had waited days for this moment, sleeping on straw and bread crusts, praying with clenched teeth.

The carriage slowed, hemmed in by wagons and pedestrians. Rain slicked the windows, and the guards rode ahead unaware. Ravaillac stepped forward, ducked beneath the wheel arch, and thrust his arm through the carriage window before anyone could shout.

Steel kissed flesh, twice. Henry gasped—not with fear, but surprise. He had survived wars, rebellions, and four assassination attempts. This final act came silent and sudden, like a whisper cut short. Blood painted the seat red. He clutched his chest, his eyes widening not with rage, but with something gentler—regret, perhaps.

As the commotion erupted, guards leapt from horses, dragging Ravaillac away as he screamed about Rome and righteousness. Shops shuttered. Windows leaned out with pale faces. In the Louvre, bells began to toll.

The Edict of Nantes remained ink on parchment, but the spirit of it flickered in the hearts Henry had led. He had been no perfect man—ambitious, worldly, a lover of many—but he had grasped the message of Romans 12:18: “If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone.”

He had brokered peace not through domination, but concession. Catholic cardinals had called him traitor for dining with Protestant lords. Huguenot preachers had denounced his mass. Yet he had persisted, believing France could stand, if not one in creed, then one in purpose. His reign proved that enemies could become neighbors.

The fragility of that peace tore open with his death. Without Henry’s steady hand, the balance trembled. His son, Louis XIII, too young to rule. Regent queens and merciless ministers would cast the country back into suspicion, until the Edict itself was revoked decades later. But the memory of Henry’s France lingered—in children not taught to hate across pulpits, in towns rebuilt instead of razed.

Not far from the Place des Vosges, where Huguenot merchants once traded openly under royal protection, candles were lit in quiet windows that day. Both Catholic and Protestant mothers clutched their sons tighter, fearing the wind of violence would return. In churches across France, prayers rose in uneasy harmony. Despite the sharp blade, the greater triumph remained: for a time, the lion had lain beside the lamb.

The streets of Paris flowed not with war cries, but weeping. A crown had fallen, but peace did not die with the man. Faith—true, humble faith—had taught a king to listen rather than command, to forgive instead of retaliate. That lesson, though costly, was not lost.

Even as blood marked the stones, something else took root. A generation that had tasted peace could not forget it. And in that, Henry’s legacy endured. As Romans had told—if it’s possible, as far as it depends on you—live at peace. Henry had made it his life’s work.

Even if the dagger struck him down, it could not undo what he had built.