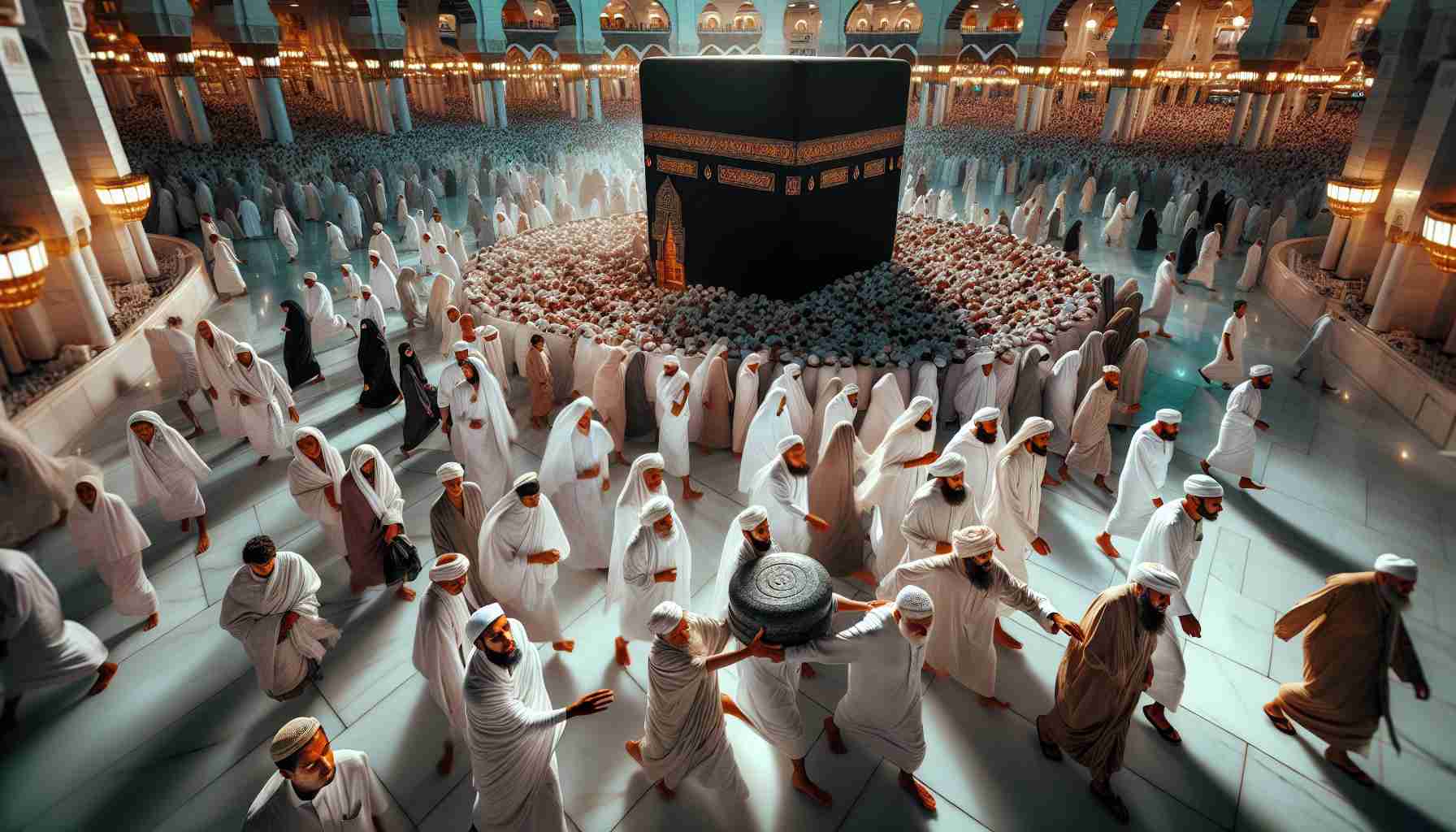

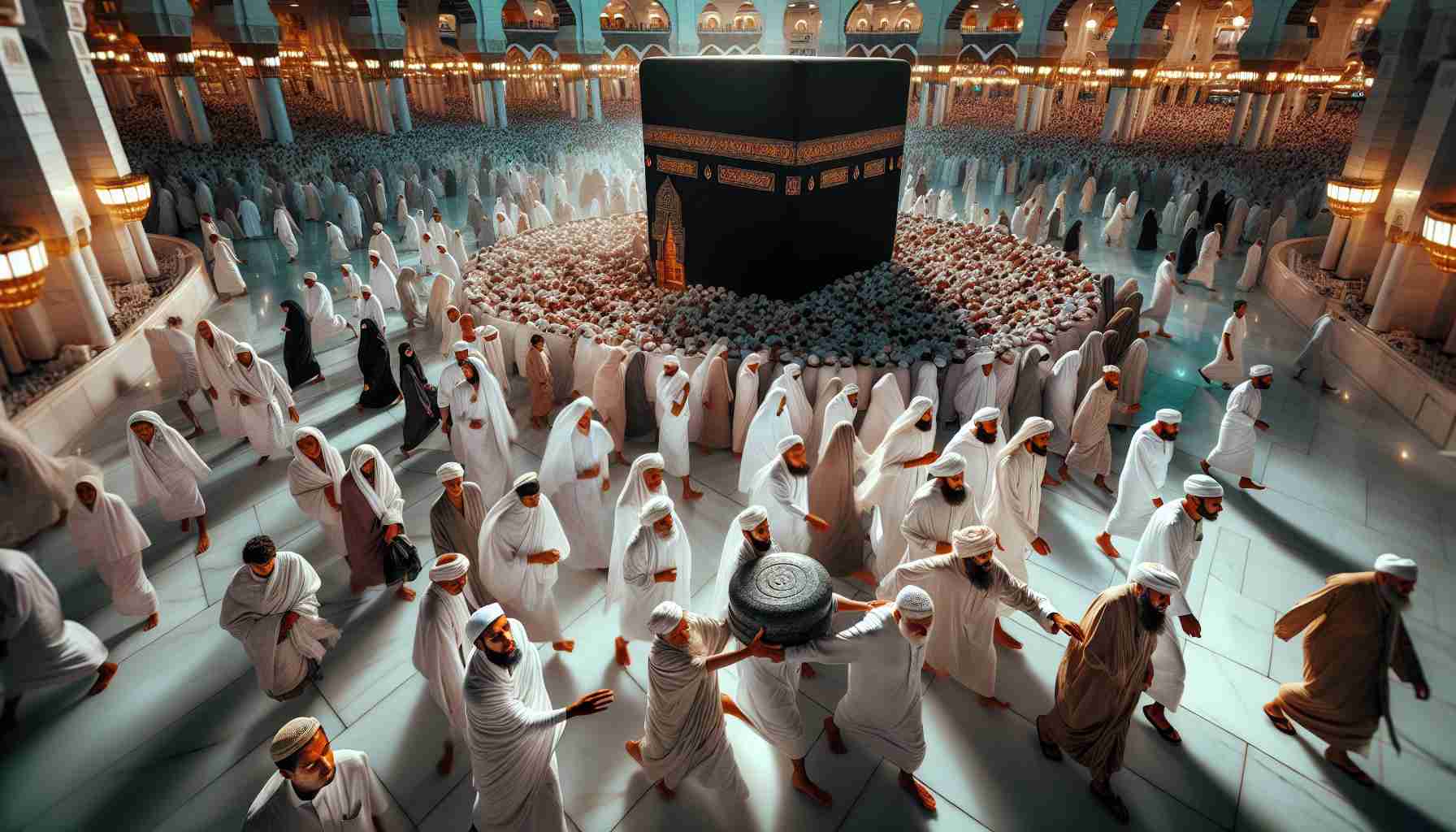

A hot wind stirred the dust along the wide courtyard, as pilgrims shuffled barefoot across gleaming white marble, their garments clinging to sun-slicked skin. In the center of their orbit stood the Kaaba—its black-draped walls catching light like flowing ink, simple yet immense, humble yet unyielding. They came from every direction, speaking every tongue, but each faced the same cube. And in its eastern corner, encased in silver, nestled a relic older than Abraham: al-Hajar al-Aswad—the Black Stone.

The boy from Yemen watched it glisten. His grandfather had told him that to touch it was to touch Heaven. But ropes and guards kept the masses back. He saw strong men weep when they failed. He had no illusions.

In the time before prophets spoke and cities rose, legend told of a rock forged not on Earth. Some claimed it fell from Paradise, brought down by angels for Adam to build his first temple. Others whispered it arrived as a meteorite—its fire staining the desert sky. Either way, it became sacred long before Quraysh tribes ruled Mecca.

Generations passed. Abraham, patriarch of monotheism, walked this land alongside Ishmael. Together, fathers of faith rebuilt the cube, raising its walls in silence. When the time came to place the Black Stone in its corner, Abraham held it in his palm. Scripture says, “And when Abraham raised the foundation of the House with Ishmael, [he prayed]: Our Lord, accept [this] from us” (Qur’an 2:127). Legends say the stone was dazzling then, a luminous white. Human sin, over centuries, turned it black.

Now, more than a thousand years after the Prophet Muhammad set it in its current place with a cloak and wise judgment, the stone remained a mystery in stone. No one could fully explain its origin. Even scientists disagreed—some pointing to meteoritic qualities, others to volcanic material. The mystery added reverence. The stone sat only a few feet above ground, worn and smooth, its dark surface kissed by countless lips, pressed by longing foreheads, traced by the trembling hands of those who reached its curve.

The boy stared. He had walked seven times around the Kaaba with his family. They had called out praises, whispered prayers, reheated old tears. Now, the final rite neared: the attempt to touch what so few could.

A wave of motion shook the crowd. A guard grunted. A man lunged forward, throwing an elbow, shouting Allahu akbar, hoarse with joy. A woman sobbed when she missed her moment. The boy's mother shielded his eyes.

But his grandfather pushed ahead. Small though he was, his steps cut a narrow path. With a hush of old strength, he cleared the last pilgrim with his elbow and leaned close.

He pressed his forehead to it.

Time stilled. Around him flowed the yearning millions, drawn like metal shavings to a hidden magnet, as though the very breath of Heaven sang from that darkened stone.

Later, when the boy reached the spot, the guards stepped in. They moved the crowd along with firm hands. No touching now. Perhaps not ever.

He stared at the curve of silver encasing it. Its surface, fractured and mended over centuries, bore the scars. The Qarmatians had smashed it in 930, the fanatics stealing the pieces for ransom. For twenty years it vanished. Some feared it lost. But the fragments returned and were restored—not whole, but surviving. Like faith often does.

He didn’t reach it. His fingers came close, but not close enough. Yet in his chest burned fire, not sorrow.

He had seen the Black Stone. Faced it. And all his life he would remember the way it shone, black as night, binding sky and earth, sin and forgiveness, distance and longing. He didn't need to touch it to be changed.

Centuries might pass. Kingdoms might fall. But generations would still circle that cube, each soul drawn not only by the physicality of stone or marble, but by the ache to find something eternal—something that speaks of Paradise lost and sought again.

Pilgrims would continue to reach, to strain with hope. And though few would touch that ancient stone, all would feel its pull.

A hot wind stirred the dust along the wide courtyard, as pilgrims shuffled barefoot across gleaming white marble, their garments clinging to sun-slicked skin. In the center of their orbit stood the Kaaba—its black-draped walls catching light like flowing ink, simple yet immense, humble yet unyielding. They came from every direction, speaking every tongue, but each faced the same cube. And in its eastern corner, encased in silver, nestled a relic older than Abraham: al-Hajar al-Aswad—the Black Stone.

The boy from Yemen watched it glisten. His grandfather had told him that to touch it was to touch Heaven. But ropes and guards kept the masses back. He saw strong men weep when they failed. He had no illusions.

In the time before prophets spoke and cities rose, legend told of a rock forged not on Earth. Some claimed it fell from Paradise, brought down by angels for Adam to build his first temple. Others whispered it arrived as a meteorite—its fire staining the desert sky. Either way, it became sacred long before Quraysh tribes ruled Mecca.

Generations passed. Abraham, patriarch of monotheism, walked this land alongside Ishmael. Together, fathers of faith rebuilt the cube, raising its walls in silence. When the time came to place the Black Stone in its corner, Abraham held it in his palm. Scripture says, “And when Abraham raised the foundation of the House with Ishmael, [he prayed]: Our Lord, accept [this] from us” (Qur’an 2:127). Legends say the stone was dazzling then, a luminous white. Human sin, over centuries, turned it black.

Now, more than a thousand years after the Prophet Muhammad set it in its current place with a cloak and wise judgment, the stone remained a mystery in stone. No one could fully explain its origin. Even scientists disagreed—some pointing to meteoritic qualities, others to volcanic material. The mystery added reverence. The stone sat only a few feet above ground, worn and smooth, its dark surface kissed by countless lips, pressed by longing foreheads, traced by the trembling hands of those who reached its curve.

The boy stared. He had walked seven times around the Kaaba with his family. They had called out praises, whispered prayers, reheated old tears. Now, the final rite neared: the attempt to touch what so few could.

A wave of motion shook the crowd. A guard grunted. A man lunged forward, throwing an elbow, shouting Allahu akbar, hoarse with joy. A woman sobbed when she missed her moment. The boy's mother shielded his eyes.

But his grandfather pushed ahead. Small though he was, his steps cut a narrow path. With a hush of old strength, he cleared the last pilgrim with his elbow and leaned close.

He pressed his forehead to it.

Time stilled. Around him flowed the yearning millions, drawn like metal shavings to a hidden magnet, as though the very breath of Heaven sang from that darkened stone.

Later, when the boy reached the spot, the guards stepped in. They moved the crowd along with firm hands. No touching now. Perhaps not ever.

He stared at the curve of silver encasing it. Its surface, fractured and mended over centuries, bore the scars. The Qarmatians had smashed it in 930, the fanatics stealing the pieces for ransom. For twenty years it vanished. Some feared it lost. But the fragments returned and were restored—not whole, but surviving. Like faith often does.

He didn’t reach it. His fingers came close, but not close enough. Yet in his chest burned fire, not sorrow.

He had seen the Black Stone. Faced it. And all his life he would remember the way it shone, black as night, binding sky and earth, sin and forgiveness, distance and longing. He didn't need to touch it to be changed.

Centuries might pass. Kingdoms might fall. But generations would still circle that cube, each soul drawn not only by the physicality of stone or marble, but by the ache to find something eternal—something that speaks of Paradise lost and sought again.

Pilgrims would continue to reach, to strain with hope. And though few would touch that ancient stone, all would feel its pull.