The sound of hammers had long ceased echoing through the valley when the first torches flickered inside the nave. Beneath its vaulted stone ribs, dusk thickened into silence. Builders had laid the final keystone of Chartres Cathedral late in the summer of 1220, sealing not just the structure but centuries of devotion, ruin, and persistence. The cathedral rose on the bones of older churches—four, some said, each one claimed by fire or war—until this one, this final creation, dared reach higher than any before.

Stone kings stared from the grand façade, their faces worn by wind yet solemn and vigilant. Pilgrims arrived on their knees, dusty from miles of penance, eyes lifted not toward the towers—as lances as they seemed—but toward the rose window that flamed even in lightless hours, a disc of glass that held the heavens.

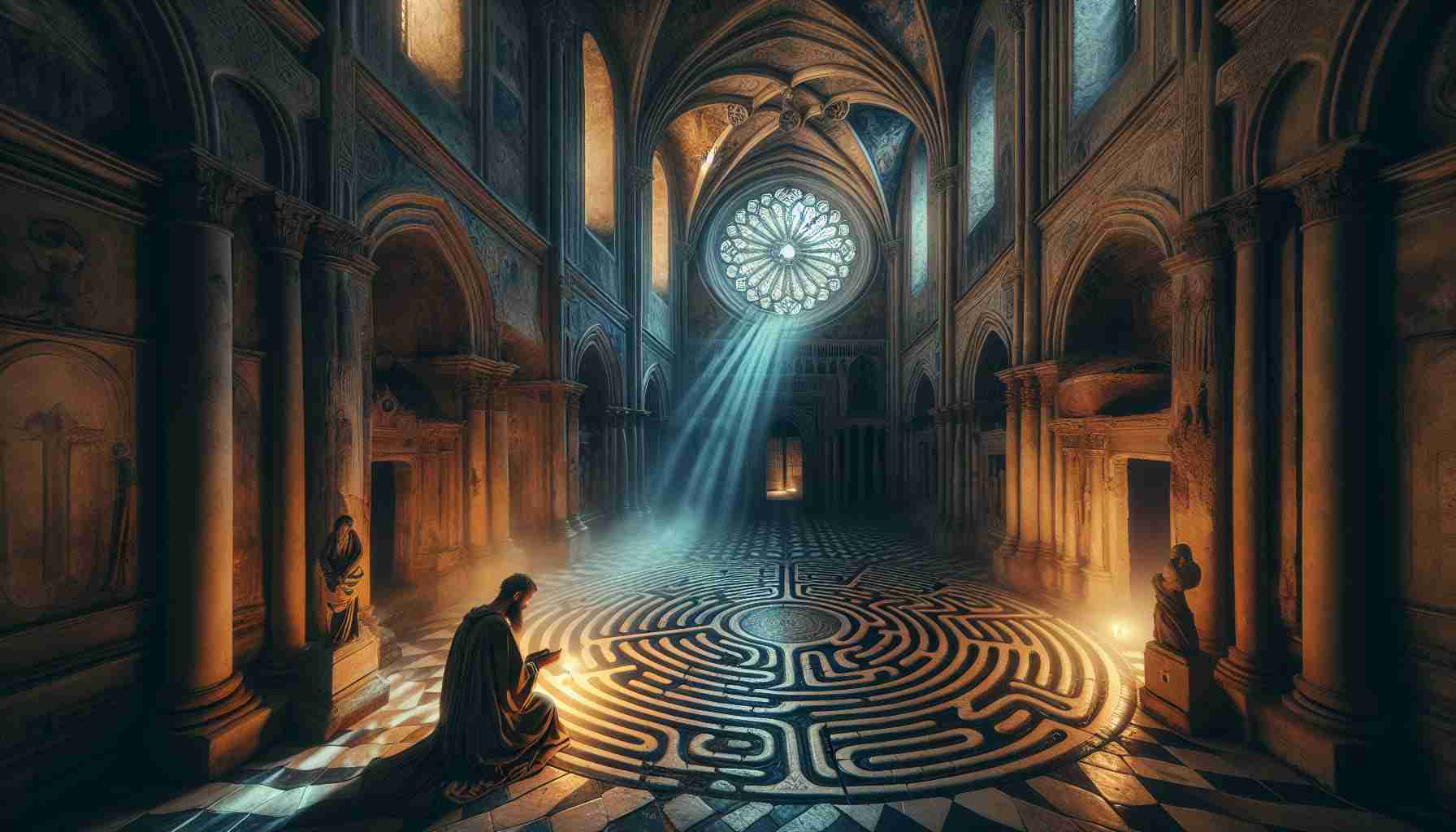

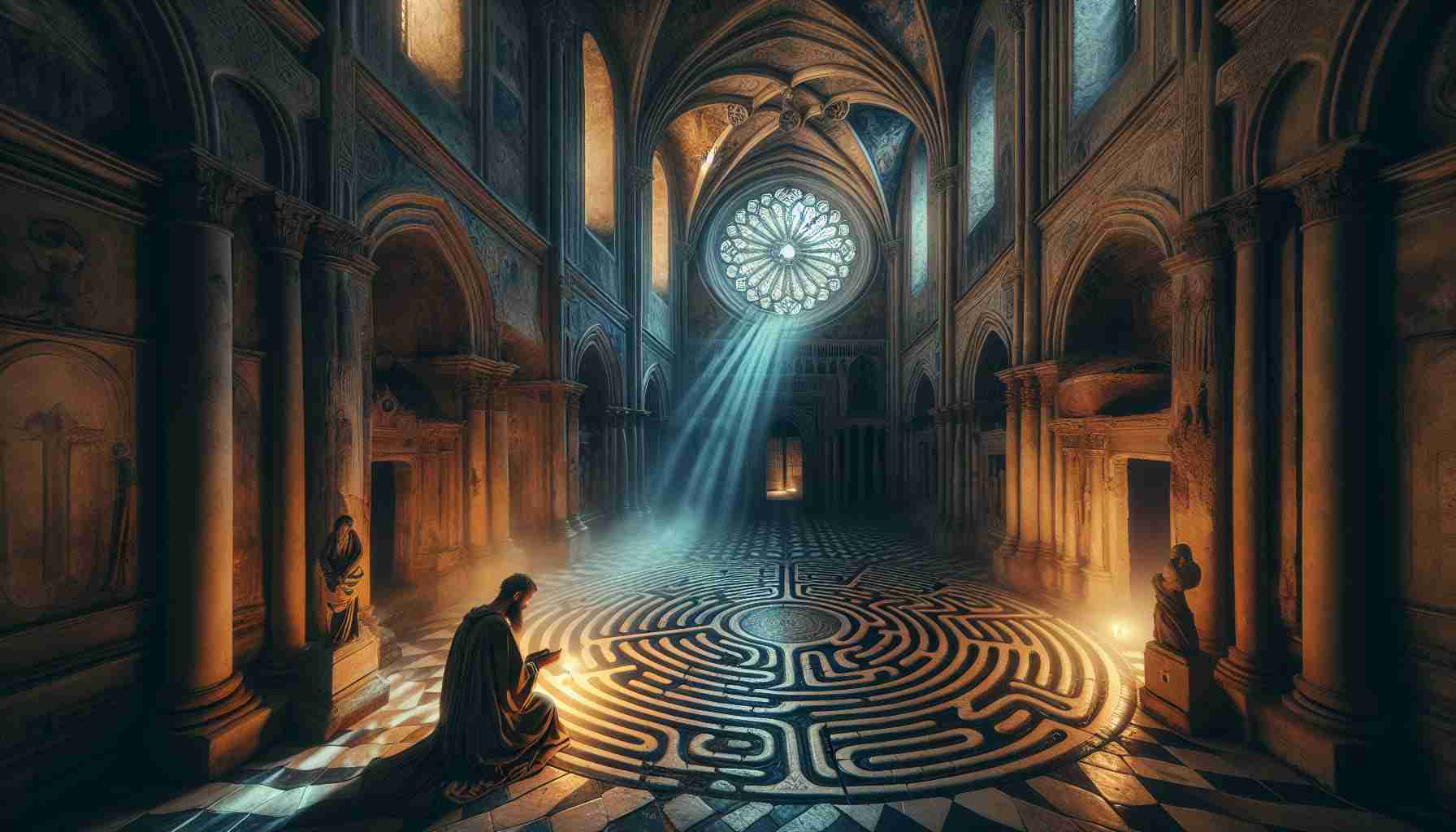

But it was the labyrinth underfoot that unnerved as much as inspired. Carved into the nave’s flagstone in a mosaic of pale limestone and blue-black shale, it whispered questions older than the gospel sung from the choir. No one walked it idly. Some priests refused to discuss it. Others claimed the stones beneath held secrets sealed before the Crusades, when knights still bore blood and palm leaves from Jerusalem.

In the spring of 1194, a fire had gutted the earlier cathedral, leaving only the crypt and west towers. As ashes smoldered in the choir, the faithful searched the rubble for the Sancta Camisia—the Virgin’s veil, said to have been worn by Mary at Christ’s birth. It was found unscathed in the crypt. To the people of Chartres, it was no survival. It was a miracle.

From those embers rose a new vision of sacred geometry. Builders spoke of divine ratios, aligning each arch and pillar with the stars. The labyrinth was laid in that same spirit. Pilgrims, forbidden from visiting the Holy Land after its capture by Saladin, were told to walk its path instead. Eleven concentric circles, winding inward, stood in for the journey to Jerusalem. At the center: salvation—or mystery.

Some whispered more. That the labyrinth concealed the hiding place of forgotten relics, even relics not meant to be revered. That the Knights Templar had left markings in the stone, sigils seen only under candlelight, maps of some subterranean vault beneath the cathedral’s hill. They pointed to the crypt again, where pagan springs once fed Druid rites. Bible met bedrock there, and faith drank from both.

Canon Étienne, keeper of the cathedral’s library in the late thirteenth century, had once vanished for three days beneath the sacristy. Returned pale and fevered, he spoke only in scripture: “The secret things belong to the Lord our God” (Deuteronomy 29:29). He claimed to have heard voices under the stones, singing verses not in any psalter. Laughter met his words. Then silence. Two winters later, his journals were found burned in the cloister garden, save for a single page etched with a spiral and the words “Et veritas liberabit vos”—"And the truth shall set you free" (John 8:32).

Generations passed. Revolution came with fists and flames. In 1793, Jacobins stormed the cathedral to strip it of sacred images. Statues were shattered, chalices stolen, but when they came for the labyrinth, a monk—old, nameless—stood over it. He did not move. Some say he cursed them in Latin; others say he said nothing at all. But no tools broke the stones that day. The labyrinth remained. His body was never found.

Chartres endured war again in 1939. German shells threatened but veered wide. American bombs hung above her like judgment. Only the windows of the north transept fell, and even then, survived in fragments to be reborn in glass. A U.S. army colonel, Welborn Griffith, ordered the cathedral spared, disobeying his orders until he proved it free of Nazi occupation. He died hours later, struck by fire elsewhere—but the cathedral stood.

Still, pilgrims come. They walk the labyrinth in silence, counting steps like prayers. Some break midway, tears falling, not knowing why. Others claim light moves differently at its center, that voices rise around them when none are near. The Vatican has never addressed these claims. Chartres priests nod gently yet speak of symbolism, not visions.

But behind the choir rail, past the iron gate, the original crypt breathes cool air. Arches carved by Carolingian masons bend like knees, and niches hide stone that pre-dates the apostles. In one chamber lies a well—fifty feet deep, known as the Well of Saints Forts—where once the druids cast offerings to the gods of oak and sky. The waters are gone, but one can still sense a hush beneath the crypt's stones, not quite peace, nor peril.

And above them all, the cathedral remains unmarred. Unburned. Even in the shade of revolution and war, it did not fall.

Legends gather at its walls like ivy, climbing toward light, ever unproven, yet alive. No one has walked the full measure of its mystery. Some truths, perhaps, wait too deep in the stone. Others echo in footsteps spiraling inward, where the heart beats slowest and the veil between heaven and earth thins to a breath.

The sound of hammers had long ceased echoing through the valley when the first torches flickered inside the nave. Beneath its vaulted stone ribs, dusk thickened into silence. Builders had laid the final keystone of Chartres Cathedral late in the summer of 1220, sealing not just the structure but centuries of devotion, ruin, and persistence. The cathedral rose on the bones of older churches—four, some said, each one claimed by fire or war—until this one, this final creation, dared reach higher than any before.

Stone kings stared from the grand façade, their faces worn by wind yet solemn and vigilant. Pilgrims arrived on their knees, dusty from miles of penance, eyes lifted not toward the towers—as lances as they seemed—but toward the rose window that flamed even in lightless hours, a disc of glass that held the heavens.

But it was the labyrinth underfoot that unnerved as much as inspired. Carved into the nave’s flagstone in a mosaic of pale limestone and blue-black shale, it whispered questions older than the gospel sung from the choir. No one walked it idly. Some priests refused to discuss it. Others claimed the stones beneath held secrets sealed before the Crusades, when knights still bore blood and palm leaves from Jerusalem.

In the spring of 1194, a fire had gutted the earlier cathedral, leaving only the crypt and west towers. As ashes smoldered in the choir, the faithful searched the rubble for the Sancta Camisia—the Virgin’s veil, said to have been worn by Mary at Christ’s birth. It was found unscathed in the crypt. To the people of Chartres, it was no survival. It was a miracle.

From those embers rose a new vision of sacred geometry. Builders spoke of divine ratios, aligning each arch and pillar with the stars. The labyrinth was laid in that same spirit. Pilgrims, forbidden from visiting the Holy Land after its capture by Saladin, were told to walk its path instead. Eleven concentric circles, winding inward, stood in for the journey to Jerusalem. At the center: salvation—or mystery.

Some whispered more. That the labyrinth concealed the hiding place of forgotten relics, even relics not meant to be revered. That the Knights Templar had left markings in the stone, sigils seen only under candlelight, maps of some subterranean vault beneath the cathedral’s hill. They pointed to the crypt again, where pagan springs once fed Druid rites. Bible met bedrock there, and faith drank from both.

Canon Étienne, keeper of the cathedral’s library in the late thirteenth century, had once vanished for three days beneath the sacristy. Returned pale and fevered, he spoke only in scripture: “The secret things belong to the Lord our God” (Deuteronomy 29:29). He claimed to have heard voices under the stones, singing verses not in any psalter. Laughter met his words. Then silence. Two winters later, his journals were found burned in the cloister garden, save for a single page etched with a spiral and the words “Et veritas liberabit vos”—"And the truth shall set you free" (John 8:32).

Generations passed. Revolution came with fists and flames. In 1793, Jacobins stormed the cathedral to strip it of sacred images. Statues were shattered, chalices stolen, but when they came for the labyrinth, a monk—old, nameless—stood over it. He did not move. Some say he cursed them in Latin; others say he said nothing at all. But no tools broke the stones that day. The labyrinth remained. His body was never found.

Chartres endured war again in 1939. German shells threatened but veered wide. American bombs hung above her like judgment. Only the windows of the north transept fell, and even then, survived in fragments to be reborn in glass. A U.S. army colonel, Welborn Griffith, ordered the cathedral spared, disobeying his orders until he proved it free of Nazi occupation. He died hours later, struck by fire elsewhere—but the cathedral stood.

Still, pilgrims come. They walk the labyrinth in silence, counting steps like prayers. Some break midway, tears falling, not knowing why. Others claim light moves differently at its center, that voices rise around them when none are near. The Vatican has never addressed these claims. Chartres priests nod gently yet speak of symbolism, not visions.

But behind the choir rail, past the iron gate, the original crypt breathes cool air. Arches carved by Carolingian masons bend like knees, and niches hide stone that pre-dates the apostles. In one chamber lies a well—fifty feet deep, known as the Well of Saints Forts—where once the druids cast offerings to the gods of oak and sky. The waters are gone, but one can still sense a hush beneath the crypt's stones, not quite peace, nor peril.

And above them all, the cathedral remains unmarred. Unburned. Even in the shade of revolution and war, it did not fall.

Legends gather at its walls like ivy, climbing toward light, ever unproven, yet alive. No one has walked the full measure of its mystery. Some truths, perhaps, wait too deep in the stone. Others echo in footsteps spiraling inward, where the heart beats slowest and the veil between heaven and earth thins to a breath.