Wind howled through the canyons of Cappadocia, scraping over stone ridges like a blade on parchment. Snow veiled the peaks by morning, but deep within the hidden valleys, warmth clung to the tufa cliffs—soft volcanic rock shaped by millennia and pierced by hands seeking the eternal.

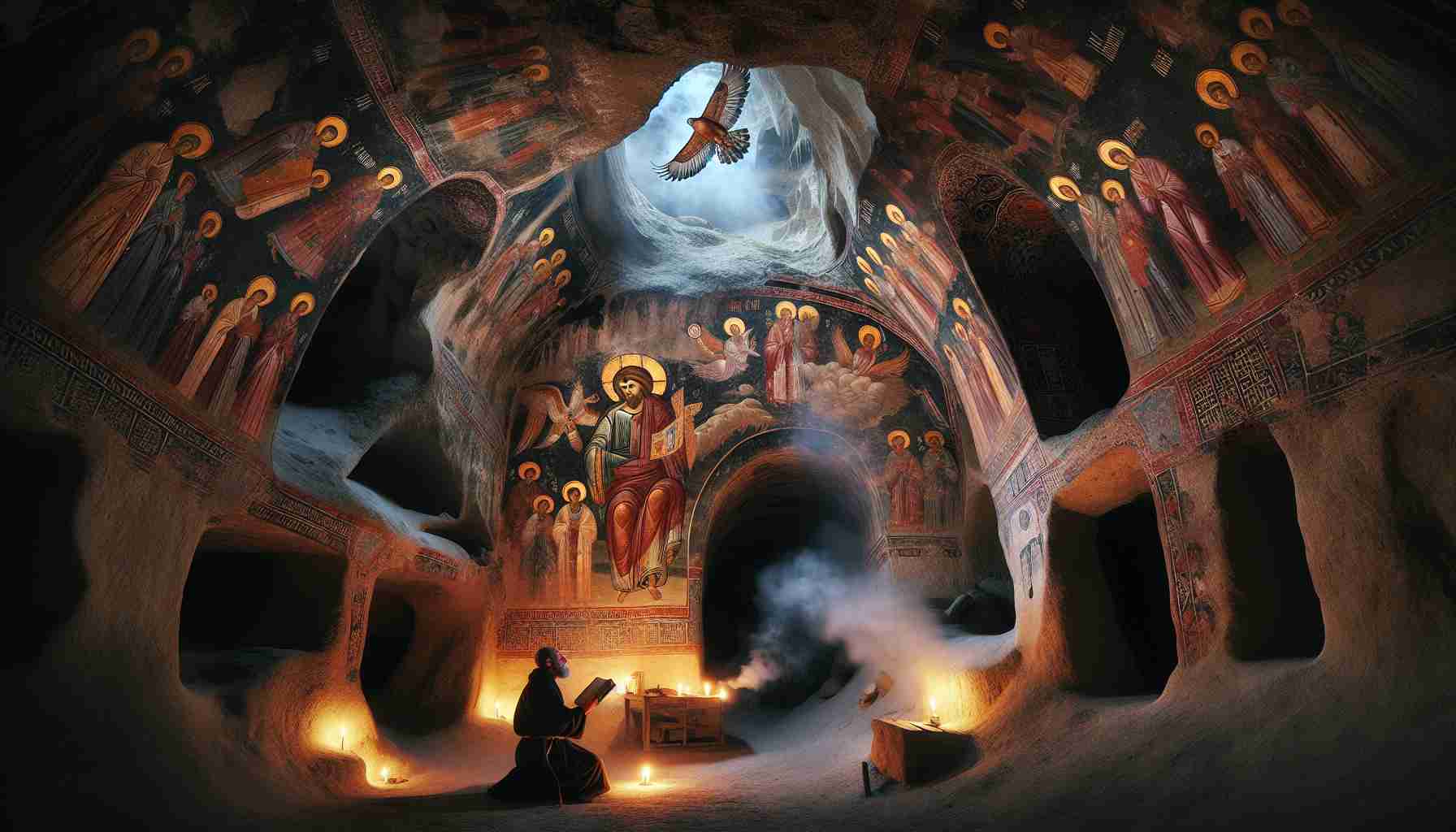

Brother Symeon pressed his palm to the curved wall inside the church chamber, breath rising in frost as he measured the dampness returning after the night. Moisture threatened the frescoes. He whispered a prayer in Greek, the words echoing against painted saints that stared at him with solemn eyes and chipped halos. Their faces—Christ Pantocrator, Mary Theotokos, the Apostles—still glowed after centuries in pigment ground from earth and fire, as if lit from within.

It was A.D. 841, and the Iconoclasts still pursued men like him—monks and scribes who defied the emperor’s decree to destroy all holy images. In Constantinople, imperial agents shattered mosaics; in Antioch, they burned scrolls. But here in Göreme, where the valleys curled like serpent paths and gullies ran deep, heaven nestled within a mountain.

He crossed into the nave, ducking beneath low arches carved with steady hands, then hurried down the narrow corridor connecting this sacred chamber to the rest of the monastic complex. Through thin chisel-dug tunnels, the scent of incense lingered. Though the world beyond shouted for silence, the monks carved their prayers into stone.

The cliff churches had no steeples. Their bells were echoes. Their towers, pigeon-topped pinnacles. From afar, strangers might see only stone. But within, ocher and emerald angels flanked crimson seraphim, icons of Daniel among lions, Jonah beneath the vine, and Christ washing feet. Each scene a confession. Each brushstroke, a defiance.

Symeon paused beneath a domed ceiling in the aptly named Dark Church. No windows pierced its hidden walls. Only lamplight ever touched the mural of the Last Supper overhead. Rumor claimed Constantine had once sent relics here, relics now deep in the lower catacombs. Others said Paul walked these valleys himself, after fleeing from Iconium (Acts 14:1–6), and preached the gospel on these stony outcrops, before the great fires or the Arab raids drove his followers underground.

Heavy boots thudded aboveground. Dust spilled from a crack in the ceiling.

He froze.

Word had come a patrol was nearing from Caesarea, questioning shepherds and demanding taxes. The monks had hidden supplies, but not the walls. Not the frescoes.

He ran.

Through a side tunnel, behind the apse, Symeon rushed into the cave that housed their oldest sanctuary. The Apple Church, it was called—an odd name born of the red sphere clutched by Michael the Archangel in the apse. Some believed it was Eden’s fruit. Others, the orb of imperial authority, surrendered at last to God. The meaning was debated even then.

He grabbed the stone-milled oil lamp and coated the opening with woven fabric, prepared to set fire to the passage if soldiers entered.

But none came.

Only silence returned.

A falcon cried in the distance. The wind died.

He knelt, breath slowing, heart pounding in his ears like a funeral drum, and stared up at the vibrant blue canopy painted above. There, Christ ascended between angels. The faces were stern, the robes caught mid-motion. The pigment shimmered faintly. This ceiling had survived tremors, raids, and time. He wondered if it would survive forgetfulness.

Later that night, the monks gathered in a hidden chamber carved into the rock’s heart. Twelve of them. They passed flat bread and diluted wine among themselves, praying in the hushed cadence only desperation could sustain. As they prayed, a boy among them—a novice named Theodoulos—asked why they painted these images, when so many said God could not be pictured.

The Abbot’s hand found the boy’s shoulder.

“We do not paint His likeness,” he said. “We paint His story. So that even when voices are silenced, the stones may still speak.”

Years passed.

The Empire shifted. Iconoclasm crumbled. Pilgrims returned to the valleys, whispering over frescoes in disbelief at their preservation. Monks came and went. Earthquakes split walls. Byzantine Greek gave way to Turkish, and churches to dovecotes.

Yet, centuries later, the Dark Church still survived, its paintings untouched by soot and sun, spared because its isolation—its darkness—had preserved its color.

And tourists, centuries removed, stepped into that ancient silence. Gasped at the sea of saints cloaked in blood-colored robes and stars of indigo and gold. Asked who painted them, and why.

But no name had been carved.

Only stories.

And prayers that once seeped into the stone.

Wind howled through the canyons of Cappadocia, scraping over stone ridges like a blade on parchment. Snow veiled the peaks by morning, but deep within the hidden valleys, warmth clung to the tufa cliffs—soft volcanic rock shaped by millennia and pierced by hands seeking the eternal.

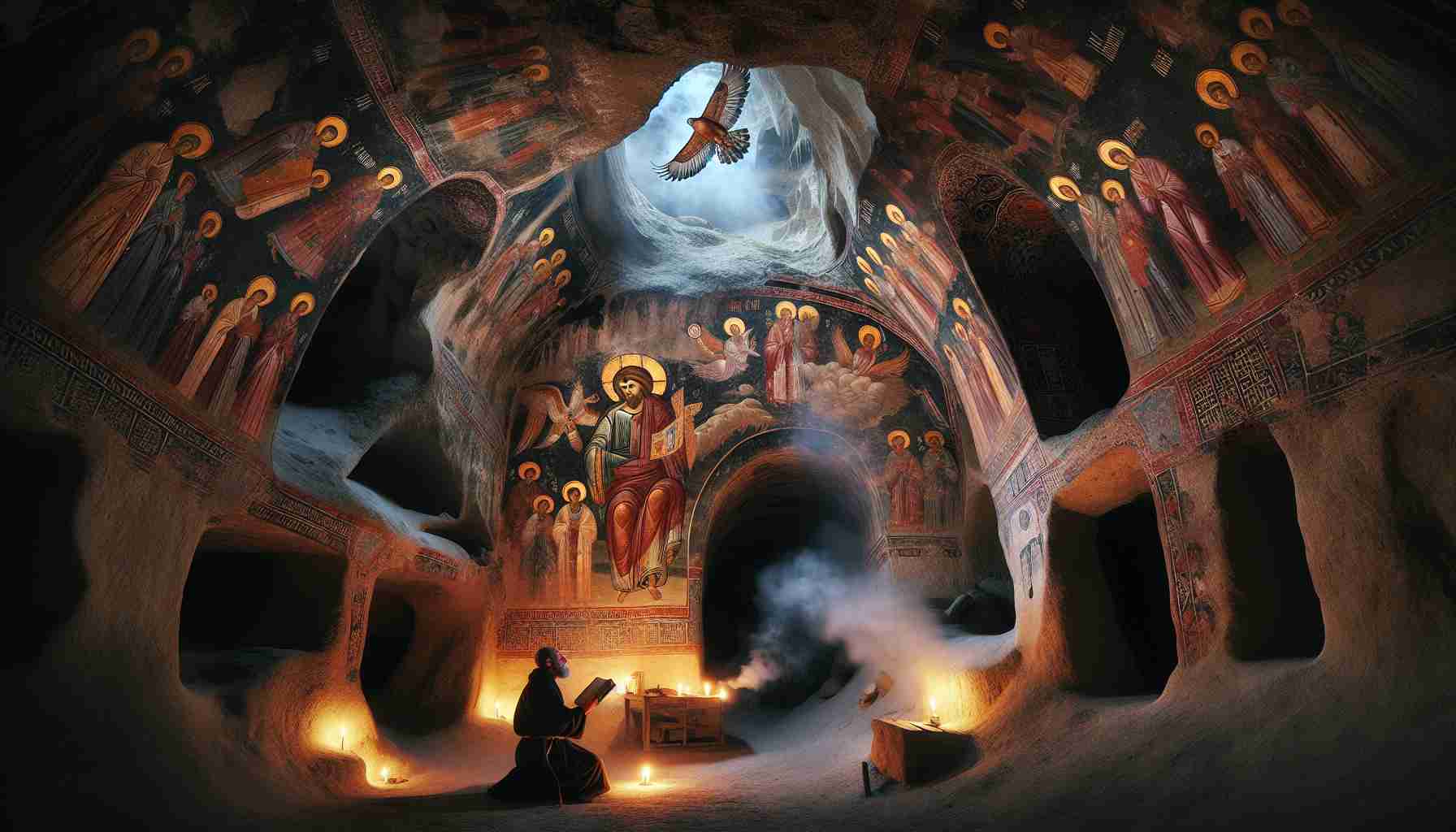

Brother Symeon pressed his palm to the curved wall inside the church chamber, breath rising in frost as he measured the dampness returning after the night. Moisture threatened the frescoes. He whispered a prayer in Greek, the words echoing against painted saints that stared at him with solemn eyes and chipped halos. Their faces—Christ Pantocrator, Mary Theotokos, the Apostles—still glowed after centuries in pigment ground from earth and fire, as if lit from within.

It was A.D. 841, and the Iconoclasts still pursued men like him—monks and scribes who defied the emperor’s decree to destroy all holy images. In Constantinople, imperial agents shattered mosaics; in Antioch, they burned scrolls. But here in Göreme, where the valleys curled like serpent paths and gullies ran deep, heaven nestled within a mountain.

He crossed into the nave, ducking beneath low arches carved with steady hands, then hurried down the narrow corridor connecting this sacred chamber to the rest of the monastic complex. Through thin chisel-dug tunnels, the scent of incense lingered. Though the world beyond shouted for silence, the monks carved their prayers into stone.

The cliff churches had no steeples. Their bells were echoes. Their towers, pigeon-topped pinnacles. From afar, strangers might see only stone. But within, ocher and emerald angels flanked crimson seraphim, icons of Daniel among lions, Jonah beneath the vine, and Christ washing feet. Each scene a confession. Each brushstroke, a defiance.

Symeon paused beneath a domed ceiling in the aptly named Dark Church. No windows pierced its hidden walls. Only lamplight ever touched the mural of the Last Supper overhead. Rumor claimed Constantine had once sent relics here, relics now deep in the lower catacombs. Others said Paul walked these valleys himself, after fleeing from Iconium (Acts 14:1–6), and preached the gospel on these stony outcrops, before the great fires or the Arab raids drove his followers underground.

Heavy boots thudded aboveground. Dust spilled from a crack in the ceiling.

He froze.

Word had come a patrol was nearing from Caesarea, questioning shepherds and demanding taxes. The monks had hidden supplies, but not the walls. Not the frescoes.

He ran.

Through a side tunnel, behind the apse, Symeon rushed into the cave that housed their oldest sanctuary. The Apple Church, it was called—an odd name born of the red sphere clutched by Michael the Archangel in the apse. Some believed it was Eden’s fruit. Others, the orb of imperial authority, surrendered at last to God. The meaning was debated even then.

He grabbed the stone-milled oil lamp and coated the opening with woven fabric, prepared to set fire to the passage if soldiers entered.

But none came.

Only silence returned.

A falcon cried in the distance. The wind died.

He knelt, breath slowing, heart pounding in his ears like a funeral drum, and stared up at the vibrant blue canopy painted above. There, Christ ascended between angels. The faces were stern, the robes caught mid-motion. The pigment shimmered faintly. This ceiling had survived tremors, raids, and time. He wondered if it would survive forgetfulness.

Later that night, the monks gathered in a hidden chamber carved into the rock’s heart. Twelve of them. They passed flat bread and diluted wine among themselves, praying in the hushed cadence only desperation could sustain. As they prayed, a boy among them—a novice named Theodoulos—asked why they painted these images, when so many said God could not be pictured.

The Abbot’s hand found the boy’s shoulder.

“We do not paint His likeness,” he said. “We paint His story. So that even when voices are silenced, the stones may still speak.”

Years passed.

The Empire shifted. Iconoclasm crumbled. Pilgrims returned to the valleys, whispering over frescoes in disbelief at their preservation. Monks came and went. Earthquakes split walls. Byzantine Greek gave way to Turkish, and churches to dovecotes.

Yet, centuries later, the Dark Church still survived, its paintings untouched by soot and sun, spared because its isolation—its darkness—had preserved its color.

And tourists, centuries removed, stepped into that ancient silence. Gasped at the sea of saints cloaked in blood-colored robes and stars of indigo and gold. Asked who painted them, and why.

But no name had been carved.

Only stories.

And prayers that once seeped into the stone.