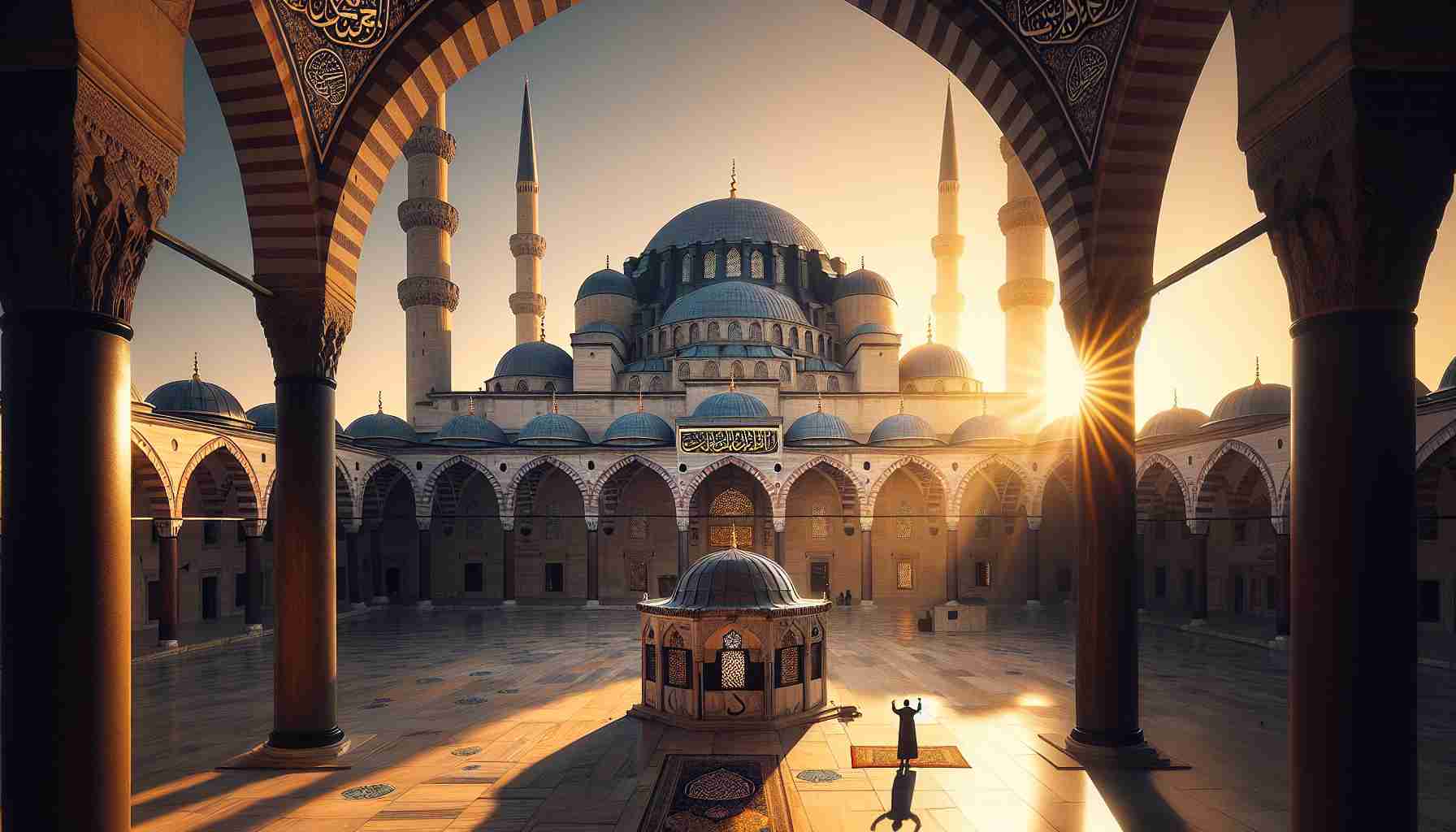

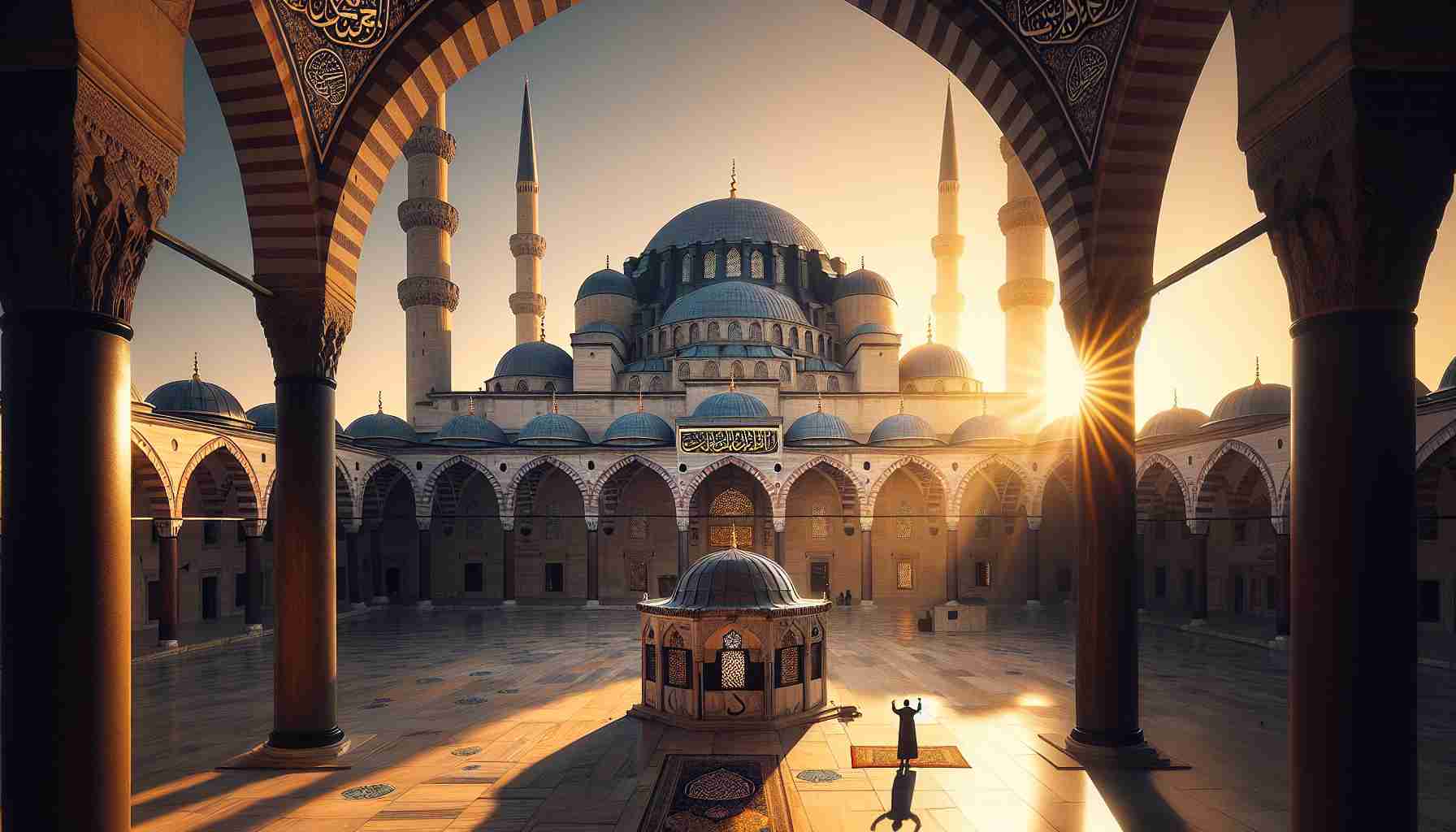

The morning sunlight struck the domes like firelight on polished bronze. In the heart of 16th-century Constantinople, the air buzzed with clamor: hammer strikes ringing against marble, ropes creaking as stones rose skyward, and the urgent shouts of foremen guiding the birth of an empire’s ambition. Atop his scaffold, the architect Mimar Sinan looked down the nave of his rising creation—the Süleymaniye Mosque—as one appraising the spine of a colossus whom he dared to rival none other than the Hagia Sophia.

Emperor Justinian’s jewel had cast its massive shadow since the sixth century. Refuge of emperors. Crown of Christendom. It was said that when Justinian first entered the Hagia Sophia—its central dome like a suspended sphere of heaven—it moved him to declare, “Solomon, I have surpassed thee.” But now, under the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, it was Islam’s turn to ascend.

Sinan, once a Christian born of the devshirme—boys taken for imperial service—had become the empire’s chief architect. He had studied the bones of the Hagia Sophia, its secrets and its scars. He had walked beneath its pendentives, run his hands along its load-bearing piers, measured the stress of centuries within its leaning walls. He knew, though none would say aloud, that the Hagia Sophia, for all her splendor, bore the fatigue of time.

Suleiman had ordered not merely a mosque, but a testament. His golden age required a crown. So, stone by stone, with Ottoman elegance married to Byzantine muscle, Sinan laid the design for Süleymaniye—not just to rival the ancient basilica but to speak in answer to it.

The blue Iznik tiles glinted with Quranic verses; delicate minarets pierced the sky like promises to God. A central dome, slightly smaller than the Hagia Sophia’s, rose with precise symmetry, flanked by semi-domes that cascaded downward like a mountain of worship. Within, a silence more powerful than chants echoed through the cavernous prayer hall, framed by 32 stained glass windows that stained light into prayer.

But awe and ambition never walk alone. In the labyrinthine streets beyond the courtyard, priests muttered of provocation. Christian merchants watched the rising dome with tight mouths. Rumors flew: the dome would collapse, the minarets would crack, that God had cursed any hand that tried to exceed His church on earth.

Yet Suleiman, known among Muslims as Kanuni—the Lawgiver—stood steady. He had read in the Injil, the Gospel still honored in Islam, of Solomon’s temple. In all monotheism, the sacred stone touched heaven. The Süleymaniye would not desecrate, but elevate.

It took seven years, each one marked by prayer and precision. Sinan labored in secret to perfect the acoustics—placing empty terracotta jars within the walls to whisper sound to every corner. His masons studied the play of humid winters and scorching summers on limestone and granite. And when plague swept the city in its fifth year, dropping thousands along the Golden Horn, work halted not one day. The laborers buried their own, then returned to carve sanctuary from sorrow.

On the day of completion, 1557, Suleiman entered the mosque, not on horseback as Justinian had, but barefoot. His eyes searched the arches, the dome, the Qibla wall pointing toward Mecca. The purity of white marble seemed to catch fire from the dome’s golden calligraphy: “He is Allah, the Creator, the Inventor, the Fashioner.”

He knelt.

No words—no proclamation or comparison. Only silence. Only prayer.

But crowds whispered. Many claimed the Süleymaniye had failed to surpass the Hagia Sophia in scale. This was true. Sinan, deep in wisdom, had not challenged the Basilica’s height but bested her in balance. The dome’s perfect harmony with its buttresses and galleries made it withstand tremors that had cracked the Hagia Sophia. Sinan’s grandson would later recall, “My master built a monument of heavenly order. But his humility would not challenge the ancients.”

There remains, to this day, a stone at the threshold of Süleymaniye engraved with no words. Some say it hides a verse from Ecclesiastes: “I have seen all the works that are done under the sun; and behold, all is vanity.” Others say it is blank, a silence etched for the One whose house it was.

In time, Istanbul forgot its outrage. The mosque fed the poor daily through its imaret. Its school raised jurists and astronomers. Its hospital treated Christian and Muslim alike. The Hagia Sophia stood across the skyline, older than ever, no longer rivaled but complemented. Two great hands lifted in different directions—but toward the same heaven.

Only Sinan knew the full truth. Twenty more years he would live, building scores of mosques and aqueducts. But near his end, he built one final sanctuary hidden within the mosque complex: a modest tomb of white stone beside Suleiman’s own. Its dome held no gold. But the stone above the arch is chiseled with a line from the Qur’an: “The life of this world is but play and amusement, but the home of the Hereafter is best for those who fear God.”

Sinan died in the shadow of his masterpiece—a man who challenged not just the heights of architecture, but those of the soul.

The morning sunlight struck the domes like firelight on polished bronze. In the heart of 16th-century Constantinople, the air buzzed with clamor: hammer strikes ringing against marble, ropes creaking as stones rose skyward, and the urgent shouts of foremen guiding the birth of an empire’s ambition. Atop his scaffold, the architect Mimar Sinan looked down the nave of his rising creation—the Süleymaniye Mosque—as one appraising the spine of a colossus whom he dared to rival none other than the Hagia Sophia.

Emperor Justinian’s jewel had cast its massive shadow since the sixth century. Refuge of emperors. Crown of Christendom. It was said that when Justinian first entered the Hagia Sophia—its central dome like a suspended sphere of heaven—it moved him to declare, “Solomon, I have surpassed thee.” But now, under the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, it was Islam’s turn to ascend.

Sinan, once a Christian born of the devshirme—boys taken for imperial service—had become the empire’s chief architect. He had studied the bones of the Hagia Sophia, its secrets and its scars. He had walked beneath its pendentives, run his hands along its load-bearing piers, measured the stress of centuries within its leaning walls. He knew, though none would say aloud, that the Hagia Sophia, for all her splendor, bore the fatigue of time.

Suleiman had ordered not merely a mosque, but a testament. His golden age required a crown. So, stone by stone, with Ottoman elegance married to Byzantine muscle, Sinan laid the design for Süleymaniye—not just to rival the ancient basilica but to speak in answer to it.

The blue Iznik tiles glinted with Quranic verses; delicate minarets pierced the sky like promises to God. A central dome, slightly smaller than the Hagia Sophia’s, rose with precise symmetry, flanked by semi-domes that cascaded downward like a mountain of worship. Within, a silence more powerful than chants echoed through the cavernous prayer hall, framed by 32 stained glass windows that stained light into prayer.

But awe and ambition never walk alone. In the labyrinthine streets beyond the courtyard, priests muttered of provocation. Christian merchants watched the rising dome with tight mouths. Rumors flew: the dome would collapse, the minarets would crack, that God had cursed any hand that tried to exceed His church on earth.

Yet Suleiman, known among Muslims as Kanuni—the Lawgiver—stood steady. He had read in the Injil, the Gospel still honored in Islam, of Solomon’s temple. In all monotheism, the sacred stone touched heaven. The Süleymaniye would not desecrate, but elevate.

It took seven years, each one marked by prayer and precision. Sinan labored in secret to perfect the acoustics—placing empty terracotta jars within the walls to whisper sound to every corner. His masons studied the play of humid winters and scorching summers on limestone and granite. And when plague swept the city in its fifth year, dropping thousands along the Golden Horn, work halted not one day. The laborers buried their own, then returned to carve sanctuary from sorrow.

On the day of completion, 1557, Suleiman entered the mosque, not on horseback as Justinian had, but barefoot. His eyes searched the arches, the dome, the Qibla wall pointing toward Mecca. The purity of white marble seemed to catch fire from the dome’s golden calligraphy: “He is Allah, the Creator, the Inventor, the Fashioner.”

He knelt.

No words—no proclamation or comparison. Only silence. Only prayer.

But crowds whispered. Many claimed the Süleymaniye had failed to surpass the Hagia Sophia in scale. This was true. Sinan, deep in wisdom, had not challenged the Basilica’s height but bested her in balance. The dome’s perfect harmony with its buttresses and galleries made it withstand tremors that had cracked the Hagia Sophia. Sinan’s grandson would later recall, “My master built a monument of heavenly order. But his humility would not challenge the ancients.”

There remains, to this day, a stone at the threshold of Süleymaniye engraved with no words. Some say it hides a verse from Ecclesiastes: “I have seen all the works that are done under the sun; and behold, all is vanity.” Others say it is blank, a silence etched for the One whose house it was.

In time, Istanbul forgot its outrage. The mosque fed the poor daily through its imaret. Its school raised jurists and astronomers. Its hospital treated Christian and Muslim alike. The Hagia Sophia stood across the skyline, older than ever, no longer rivaled but complemented. Two great hands lifted in different directions—but toward the same heaven.

Only Sinan knew the full truth. Twenty more years he would live, building scores of mosques and aqueducts. But near his end, he built one final sanctuary hidden within the mosque complex: a modest tomb of white stone beside Suleiman’s own. Its dome held no gold. But the stone above the arch is chiseled with a line from the Qur’an: “The life of this world is but play and amusement, but the home of the Hereafter is best for those who fear God.”

Sinan died in the shadow of his masterpiece—a man who challenged not just the heights of architecture, but those of the soul.