The sun had not yet risen, but the forest was already awake. Cicadas hummed around the base of the Bodhi tree, their rhythm calm and steady. Underneath the tree sat Siddhartha Gautama, the man who would become the Buddha. He had once been a prince, wrapped in silks and guarded from suffering, but now he wore the humble robes of a monk and lived with only the basics needed to survive. He had seen pain, sickness, old age, and death—questions about life had driven him to seek the truth.

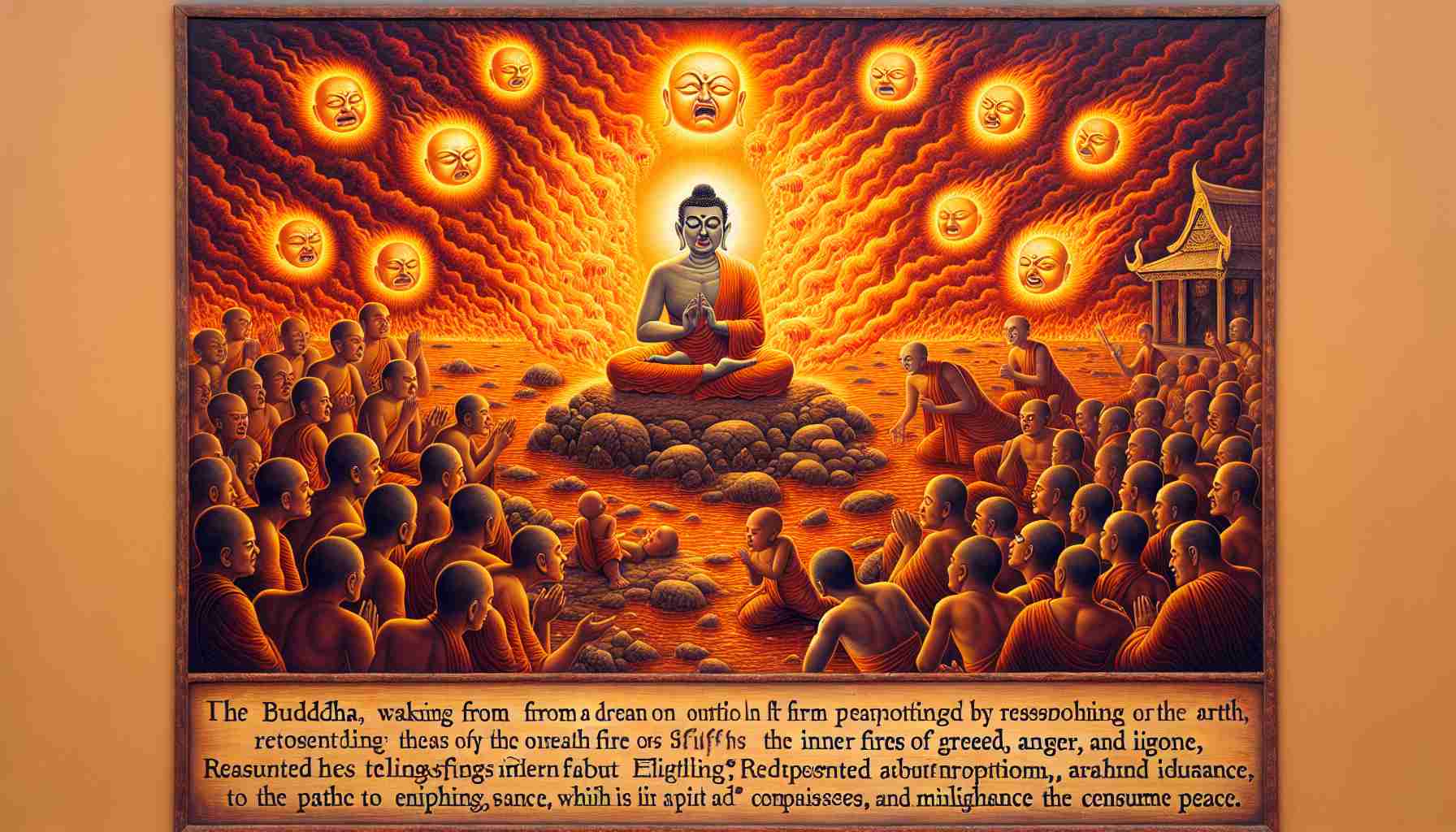

That morning, before the first light touched the trees, the Buddha had a dream. His eyes had been closed in meditation all through the night, but inside his mind, a vision unfolded. In the dream, one sun rose into the sky. Then a second. Then a third. One after another, seven suns climbed into the heavens until the light became harsh, blinding, unbearable. Rivers dried up. Crops turned to ash. People and animals ran in fear, trying to hide from the heat, but there was no shadow left under all those suns.

It was a dream of destruction, but unlike a nightmare filled with panic, the Buddha felt no fear. When he opened his eyes, he simply stood up, gathered his robe around his shoulders, and began walking toward the town of Jetavana, where his disciples were waiting.

Later that day, as the monks assembled around him, one of them approached. It was Ananda, the Buddha’s cousin and closest attendant—a kind-hearted man who always asked the questions that others were too shy to speak.

“Master,” Ananda said quietly, “we heard you stirred before dawn. Was there a vision?”

The Buddha nodded and shared the dream.

The monks fell silent, troubled.

“Tell us, Master,” one of them said, “are we to fear this dream? Seven suns—does this mean the end of the world?”

The Buddha looked around at his disciples—some young, others old and weathered—and sat before them.

“This dream,” he said, “is not a sign to fear, but one to understand.”

He told them that the suns symbolized the fires that rise in all sentient beings when mindfulness is lost—fires of greed, anger, and ignorance. As these inner suns grow stronger, they consume the peace of the world. Water, which gives life, dries. Trees, which offer shelter, are scorched. People begin to suffer, not from the outside first, but from within.

“But there is a way to cool the world,” he said. “When a person truly sees that nothing is permanent, that all things rise and fall, they learn to let go. When we let go, we stop feeding those inner flames.”

The monks listened closely. The youngest of them, named Rahula, the Buddha’s own son who had joined the monastic path, asked, “But Father, if everything disappears, even the world, isn’t that a reason for sadness?”

“No,” the Buddha replied gently, “for in emptiness, we find the greatest gift: freedom. What disappears was never ours to hold. When we stop clinging, we stop suffering.”

That evening, as the sun set—just one sun, not seven—Rahula sat by himself near the edge of the forest. He listened to the wind and watched as the orange sky faded into deep blue. He thought about his father’s calm voice, about the meaning of detachment, and he began to understand.

Emptiness wasn’t a punishment. It was a quiet invitation to live with compassion. To be mindful of what truly mattered. To not burn with desire for things that change or fade.

And so from that silent turning point—a dream where the world nearly burned—came a teaching that cooled the hearts of generations. Let go, be awake, act with kindness.

And you will find peace.

The sun had not yet risen, but the forest was already awake. Cicadas hummed around the base of the Bodhi tree, their rhythm calm and steady. Underneath the tree sat Siddhartha Gautama, the man who would become the Buddha. He had once been a prince, wrapped in silks and guarded from suffering, but now he wore the humble robes of a monk and lived with only the basics needed to survive. He had seen pain, sickness, old age, and death—questions about life had driven him to seek the truth.

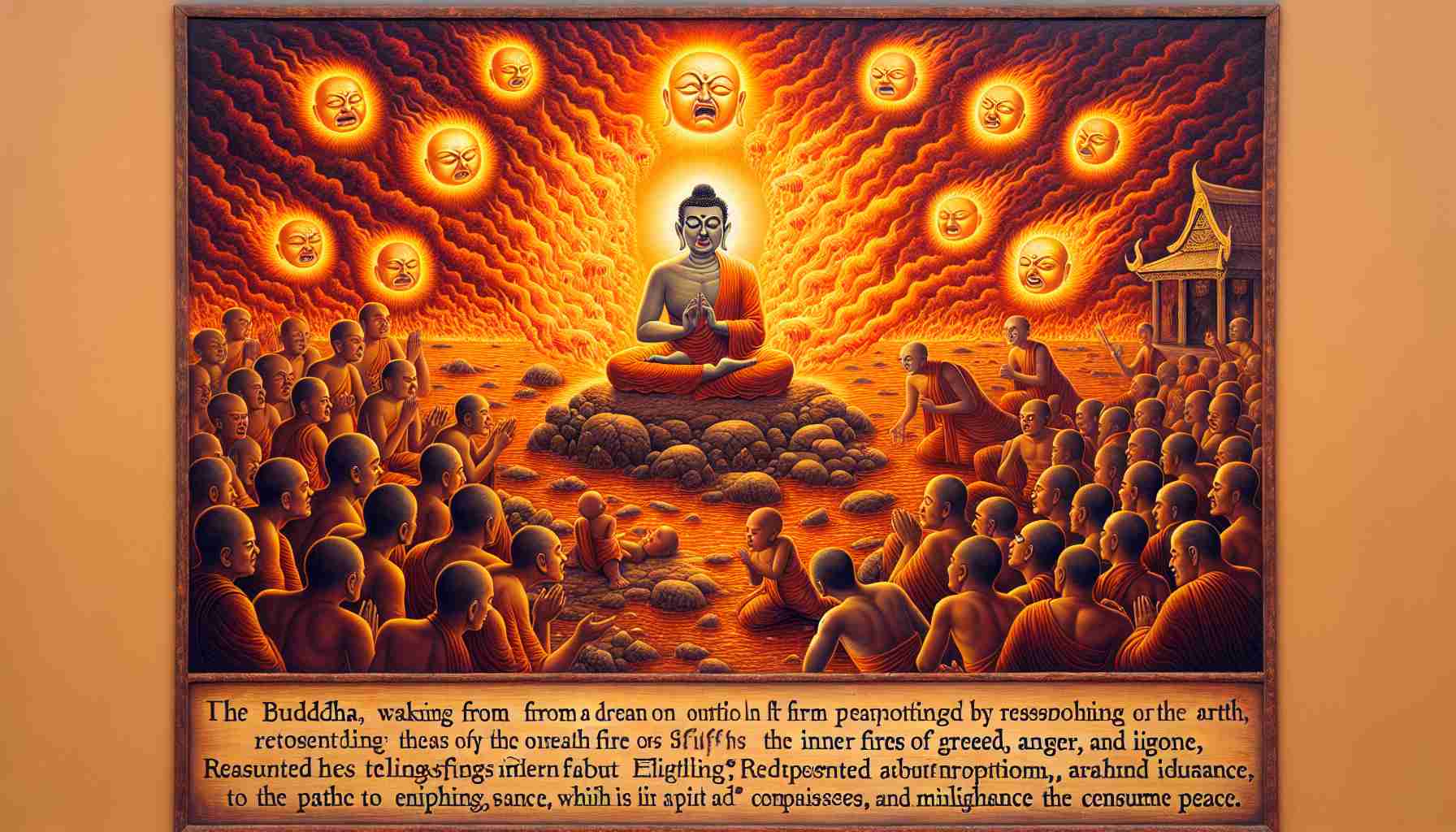

That morning, before the first light touched the trees, the Buddha had a dream. His eyes had been closed in meditation all through the night, but inside his mind, a vision unfolded. In the dream, one sun rose into the sky. Then a second. Then a third. One after another, seven suns climbed into the heavens until the light became harsh, blinding, unbearable. Rivers dried up. Crops turned to ash. People and animals ran in fear, trying to hide from the heat, but there was no shadow left under all those suns.

It was a dream of destruction, but unlike a nightmare filled with panic, the Buddha felt no fear. When he opened his eyes, he simply stood up, gathered his robe around his shoulders, and began walking toward the town of Jetavana, where his disciples were waiting.

Later that day, as the monks assembled around him, one of them approached. It was Ananda, the Buddha’s cousin and closest attendant—a kind-hearted man who always asked the questions that others were too shy to speak.

“Master,” Ananda said quietly, “we heard you stirred before dawn. Was there a vision?”

The Buddha nodded and shared the dream.

The monks fell silent, troubled.

“Tell us, Master,” one of them said, “are we to fear this dream? Seven suns—does this mean the end of the world?”

The Buddha looked around at his disciples—some young, others old and weathered—and sat before them.

“This dream,” he said, “is not a sign to fear, but one to understand.”

He told them that the suns symbolized the fires that rise in all sentient beings when mindfulness is lost—fires of greed, anger, and ignorance. As these inner suns grow stronger, they consume the peace of the world. Water, which gives life, dries. Trees, which offer shelter, are scorched. People begin to suffer, not from the outside first, but from within.

“But there is a way to cool the world,” he said. “When a person truly sees that nothing is permanent, that all things rise and fall, they learn to let go. When we let go, we stop feeding those inner flames.”

The monks listened closely. The youngest of them, named Rahula, the Buddha’s own son who had joined the monastic path, asked, “But Father, if everything disappears, even the world, isn’t that a reason for sadness?”

“No,” the Buddha replied gently, “for in emptiness, we find the greatest gift: freedom. What disappears was never ours to hold. When we stop clinging, we stop suffering.”

That evening, as the sun set—just one sun, not seven—Rahula sat by himself near the edge of the forest. He listened to the wind and watched as the orange sky faded into deep blue. He thought about his father’s calm voice, about the meaning of detachment, and he began to understand.

Emptiness wasn’t a punishment. It was a quiet invitation to live with compassion. To be mindful of what truly mattered. To not burn with desire for things that change or fade.

And so from that silent turning point—a dream where the world nearly burned—came a teaching that cooled the hearts of generations. Let go, be awake, act with kindness.

And you will find peace.