The sun was warm on my back as I sat alone behind my father’s small painting shop. My name is Lin, and I was ten the year I stopped painting.

Before that, I used to love it—the sweep of the brush, the way the ink melted into the paper like rain into earth. But then the contest came. All the young painters in the village were to create a masterpiece for the Emperor’s scout, who would visit in spring.

“Paint something that shows great skill,” my father said. “Win, and you may study with the court artists in the capital.”

So day after day, I tried. I pushed my brush hard, redrawing the same tiger, the same mountain, again and again. I tore page after page, never happy. The joy that once danced in my hand was gone. I grew angry. One day, I slammed the brush down and walked away.

“I’m not good enough,” I muttered to myself. The ink bottle tipped, dripping onto my picture. A black smear bled across the page, like a flying shadow.

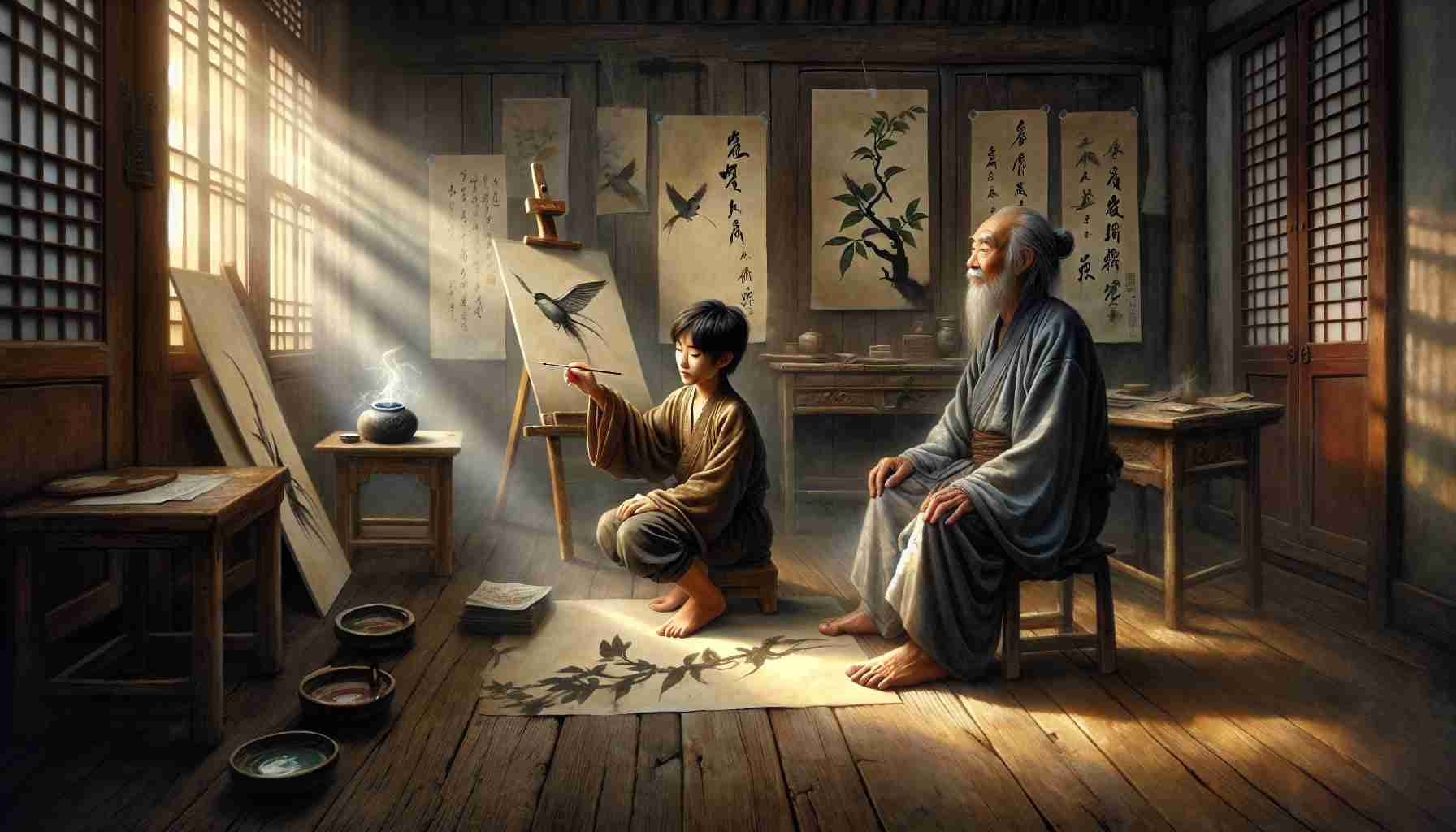

That’s when the old man appeared.

He wore a loose gray robe, his beard silver as river mist. He moved like water—quiet, smooth, and slow.

“I saw the fall of your brush,” he said, eyes crinkling. “Very dramatic.”

I flushed. “Why do you care?”

He looked at the soaked paper. “Long ago,” he said, “a man named Zhuangzi dreamed he was a butterfly. When he woke, he did not know if he was a man dreaming of butterflies, or a butterfly dreaming of being a man.”

I frowned. “What does that have to do with painting?”

“Only this,” the old man smiled. “When you try too hard, the brush no longer dances. You are too full of thoughts—like a river blocked by stones. You must become the butterfly again.”

“I don’t understand,” I grumbled.

He took a brush, dipped it in the spilled ink, and, with one soft stroke, painted a single leaf. It was... perfect. Not because it had detail or shine. But because it felt like a real leaf spinning in the wind.

“There was no plan,” he said. “The leaf came because I did not hold the brush too tightly.”

He handed the brush to me. “Let go. See what flows.”

I hesitated. Then, quietly, I took it. I closed my eyes, shut away the idea of contests and skill. I pressed the brush softly, letting it glide. A bird appeared—wing crooked, flight uncertain—but free.

For the first time in a long while, I smiled.

I didn’t win that contest. But after that day, I painted again—not to win, but to feel peace. Sometimes my landscapes danced. Sometimes they dripped. But they always felt alive.

Now, I keep that first butterfly-bird behind my desk. Whenever I try too hard, I look at it and remember: The Tao does not push or pull. It flows. And the brush—ungrasped—flies most freely.

I’m still learning to be like that brush.

The sun was warm on my back as I sat alone behind my father’s small painting shop. My name is Lin, and I was ten the year I stopped painting.

Before that, I used to love it—the sweep of the brush, the way the ink melted into the paper like rain into earth. But then the contest came. All the young painters in the village were to create a masterpiece for the Emperor’s scout, who would visit in spring.

“Paint something that shows great skill,” my father said. “Win, and you may study with the court artists in the capital.”

So day after day, I tried. I pushed my brush hard, redrawing the same tiger, the same mountain, again and again. I tore page after page, never happy. The joy that once danced in my hand was gone. I grew angry. One day, I slammed the brush down and walked away.

“I’m not good enough,” I muttered to myself. The ink bottle tipped, dripping onto my picture. A black smear bled across the page, like a flying shadow.

That’s when the old man appeared.

He wore a loose gray robe, his beard silver as river mist. He moved like water—quiet, smooth, and slow.

“I saw the fall of your brush,” he said, eyes crinkling. “Very dramatic.”

I flushed. “Why do you care?”

He looked at the soaked paper. “Long ago,” he said, “a man named Zhuangzi dreamed he was a butterfly. When he woke, he did not know if he was a man dreaming of butterflies, or a butterfly dreaming of being a man.”

I frowned. “What does that have to do with painting?”

“Only this,” the old man smiled. “When you try too hard, the brush no longer dances. You are too full of thoughts—like a river blocked by stones. You must become the butterfly again.”

“I don’t understand,” I grumbled.

He took a brush, dipped it in the spilled ink, and, with one soft stroke, painted a single leaf. It was... perfect. Not because it had detail or shine. But because it felt like a real leaf spinning in the wind.

“There was no plan,” he said. “The leaf came because I did not hold the brush too tightly.”

He handed the brush to me. “Let go. See what flows.”

I hesitated. Then, quietly, I took it. I closed my eyes, shut away the idea of contests and skill. I pressed the brush softly, letting it glide. A bird appeared—wing crooked, flight uncertain—but free.

For the first time in a long while, I smiled.

I didn’t win that contest. But after that day, I painted again—not to win, but to feel peace. Sometimes my landscapes danced. Sometimes they dripped. But they always felt alive.

Now, I keep that first butterfly-bird behind my desk. Whenever I try too hard, I look at it and remember: The Tao does not push or pull. It flows. And the brush—ungrasped—flies most freely.

I’m still learning to be like that brush.