I was just a girl with a loom, born in the dusty outskirts of Kosambi—a city once filled with traders, monks, and the hum of philosophy. My name will not be written in any royal scrolls, but I was there the day my heart untangled from anger and sorrow. I was the daughter of Maranta, a skilled weaver whose hands could coax the gods out of thread. We lived simply, spinning cloth to earn enough rice, quietly listening when monks came to teach the Dhamma.

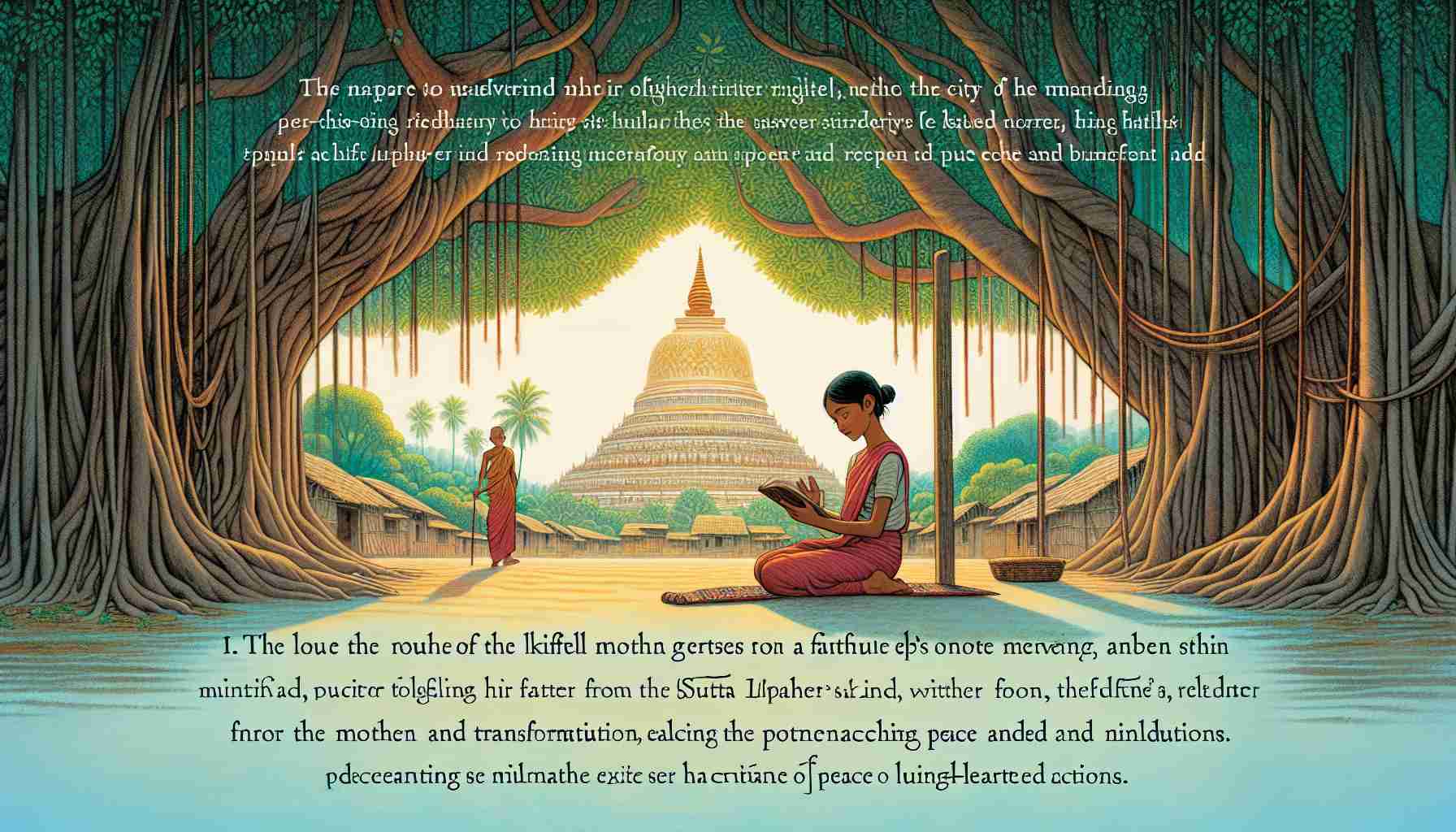

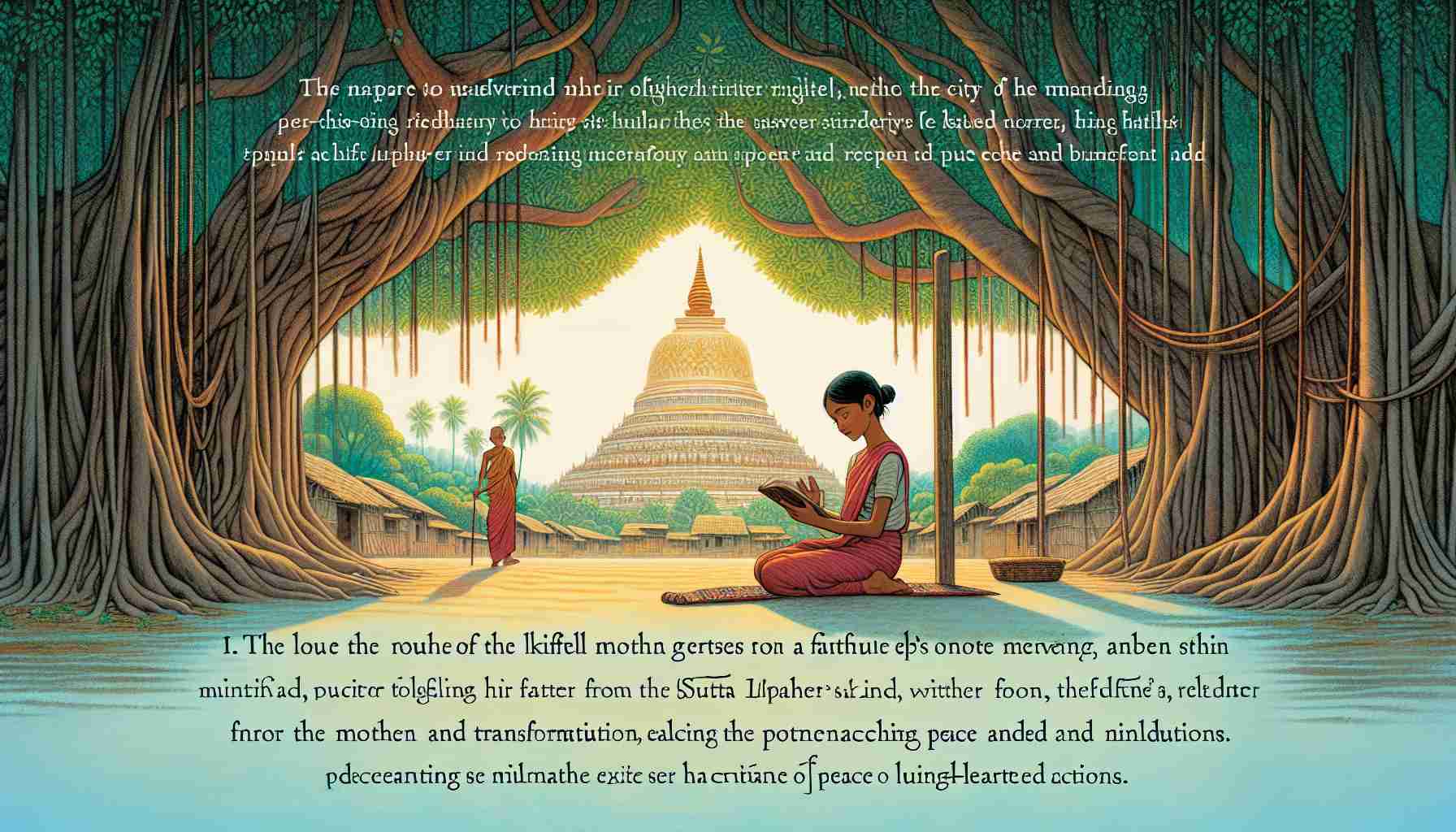

One day, I sat at the edge of the village, weaving beneath the banyan tree my father had planted when I was little. My mother had passed the previous rains, and Baba—the word I used with both affection and reverence for my father—was growing gray with grief. Only our craft kept us from sinking.

That morning, a monk approached. He was tall, with eyes like calm water and robes stained with the dust of many roads. His name was Mahakaccana, a disciple of the Buddha. He had come to Kosambi to settle disputes between rival monks—those who argued over the smallest rules while forgetting the greater truth.

The village gathered beneath the tree, where even the sparrows hushed to hear. Mahakaccana’s voice was soft, but every word was weighty, like rain falling on dry soil.

He recited a verse from the Sutta Nipāta, a collection of the Buddha’s earliest teachings. Though I didn’t know its name then, the words carved into me:

"If someone speaks or acts with a pure heart, happiness follows them like a shadow that never leaves."

The wind slowed. I looked at Baba. His face was quiet, but a tear was winding across his cheek like the river that split our village.

I didn’t yet understand the deep meanings of karma or rebirth, but something stirred inside me. I realized that I had been weaving sorrow into each thread, tying my sadness to every cloth. My mind was filled with suffering, because I did not know how to let go.

That night, I could not sleep. I sat by the loom, the moonlight threading between its wooden bars. I remembered all the times I had spoken sharply to my Baba, or neglected the village elder out of pride. Karma, they said, was not punishment—it was cause and effect. Like planting a seed and watching it bloom or wither. And mindfulness was the gardener.

The next day, I offered our best cloth to the monk. He smiled gently and accepted it—not for himself, but for someone in need. I watched as he gave it to a blind man near the river, who had no robe to keep warm. My heart lifted.

From then on, I chose to act with compassion. Not sometimes. Always. I became the thread that connected kindness across our village. My weaving changed. People came to buy my cloth not just for its softness, but the peace they said it carried. As if the mindfulness I tucked into every corner spread to their homes, too.

Years later, after Baba was gone and I had become the old woman under the banyan tree, children came to sit by me as I wove. They asked me why I smiled so easily, even when the winds were cruel.

And I told them: “Mindfulness is not escape. It is waking up. It is seeing clearly, and choosing love anyway.”

That day under the tree, I did not become wise all at once—but I did begin the journey. Because of one teaching, one monk, and one moment where I chose to listen.

And so, the teaching of the Sutta Nipāta did not drift away like old smoke. It stayed—woven into this life, and the next.

I was just a girl with a loom, born in the dusty outskirts of Kosambi—a city once filled with traders, monks, and the hum of philosophy. My name will not be written in any royal scrolls, but I was there the day my heart untangled from anger and sorrow. I was the daughter of Maranta, a skilled weaver whose hands could coax the gods out of thread. We lived simply, spinning cloth to earn enough rice, quietly listening when monks came to teach the Dhamma.

One day, I sat at the edge of the village, weaving beneath the banyan tree my father had planted when I was little. My mother had passed the previous rains, and Baba—the word I used with both affection and reverence for my father—was growing gray with grief. Only our craft kept us from sinking.

That morning, a monk approached. He was tall, with eyes like calm water and robes stained with the dust of many roads. His name was Mahakaccana, a disciple of the Buddha. He had come to Kosambi to settle disputes between rival monks—those who argued over the smallest rules while forgetting the greater truth.

The village gathered beneath the tree, where even the sparrows hushed to hear. Mahakaccana’s voice was soft, but every word was weighty, like rain falling on dry soil.

He recited a verse from the Sutta Nipāta, a collection of the Buddha’s earliest teachings. Though I didn’t know its name then, the words carved into me:

"If someone speaks or acts with a pure heart, happiness follows them like a shadow that never leaves."

The wind slowed. I looked at Baba. His face was quiet, but a tear was winding across his cheek like the river that split our village.

I didn’t yet understand the deep meanings of karma or rebirth, but something stirred inside me. I realized that I had been weaving sorrow into each thread, tying my sadness to every cloth. My mind was filled with suffering, because I did not know how to let go.

That night, I could not sleep. I sat by the loom, the moonlight threading between its wooden bars. I remembered all the times I had spoken sharply to my Baba, or neglected the village elder out of pride. Karma, they said, was not punishment—it was cause and effect. Like planting a seed and watching it bloom or wither. And mindfulness was the gardener.

The next day, I offered our best cloth to the monk. He smiled gently and accepted it—not for himself, but for someone in need. I watched as he gave it to a blind man near the river, who had no robe to keep warm. My heart lifted.

From then on, I chose to act with compassion. Not sometimes. Always. I became the thread that connected kindness across our village. My weaving changed. People came to buy my cloth not just for its softness, but the peace they said it carried. As if the mindfulness I tucked into every corner spread to their homes, too.

Years later, after Baba was gone and I had become the old woman under the banyan tree, children came to sit by me as I wove. They asked me why I smiled so easily, even when the winds were cruel.

And I told them: “Mindfulness is not escape. It is waking up. It is seeing clearly, and choosing love anyway.”

That day under the tree, I did not become wise all at once—but I did begin the journey. Because of one teaching, one monk, and one moment where I chose to listen.

And so, the teaching of the Sutta Nipāta did not drift away like old smoke. It stayed—woven into this life, and the next.