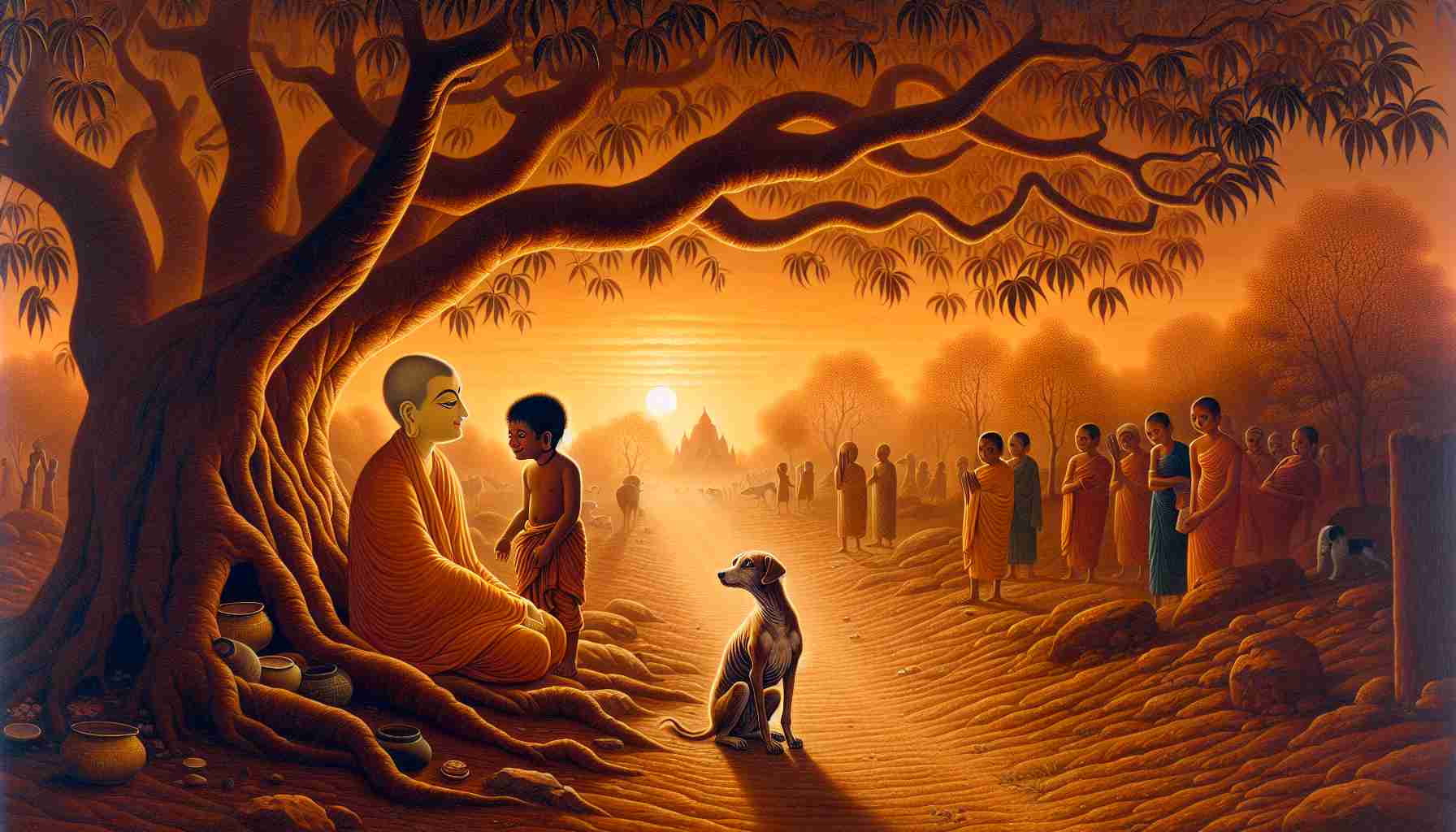

The sun hung low over the dusty road, casting long shadows from the trees above. I was just a young beggar boy then, skin taut over my bones, sleeping under bodhi leaves and eating whatever scraps kind-hearted villagers left behind. My name isn’t important—it never was. But I remember what happened the day I saw the wandering teacher, the man they called the Buddha.

Siddhartha Gautama, who would later be known as the Buddha, was born a prince in a wealthy kingdom called Kapilavatthu, in what is now southern Nepal. Though he had everything—jewels, food, fine robes—he left it all behind. Why? Because he saw suffering. And he knew deep inside that true happiness could not come from gold or power, but from wisdom. That was how he came to wander the forests and villages of India, teaching what he had discovered about life, death, and rebirth.

I had seen him before from afar—calm, barefoot, followed by monks in faded robes—but this day was different.

He had stopped at the edge of the village where I lay under a mango tree. Close by, a dog whimpered. Its bones jutted outward, and flies gathered at its eyes. No one had helped it. Many villagers believed such animals were the result of bad karma—that in another life, it may have been cruel or selfish, and now it was paying the price. They looked away, afraid and judgmental.

But the Buddha did not turn away.

He dropped to his knees beside the creature. One of his disciples, Ananda, said gently, “Master, it’s unclean. Let us move on.”

But the Buddha shook his head. “This dog suffers because of causes we do not see. Just as we once suffered because of causes we have forgotten. No being—man or animal—is without a path to liberation.”

I had never heard a man speak like that. Not about a dog. Not with such calm certainty.

The Buddha motioned to a nearby stream and asked for water. He washed the dog’s sores with care, speaking softly, like the dog could understand. Then he offered it crumbs from a bowl.

Some of the villagers gathered, whispering. “He’s wasting time,” one man said. “That animal is bound for death.”

But others grew quiet, watching him.

When the dog finally licked the crumbs and lay down peacefully, the Buddha looked up and said, “Compassion is not for those who deserve it. It is for all who suffer. If we cannot give kindness to a creature others reject, how will we treat those we fear or misunderstand?”

Years have passed, and I have long since shaved my head and taken the robes of a monk. I think of that dog often. I never knew what happened to it after that. But I knew what happened to me.

I saw that the truth the Buddha spoke wasn’t just for wise men or kings. It was for broken boys like me, and for starving dogs too.

That day, I began to understand the Dharma—not as something far away and holy, but as something as simple and as hard as kindness to all beings. That day, both the dog and I were touched by compassion.

And in that moment of shared mercy, the wheel of rebirth turned again—and something new began.

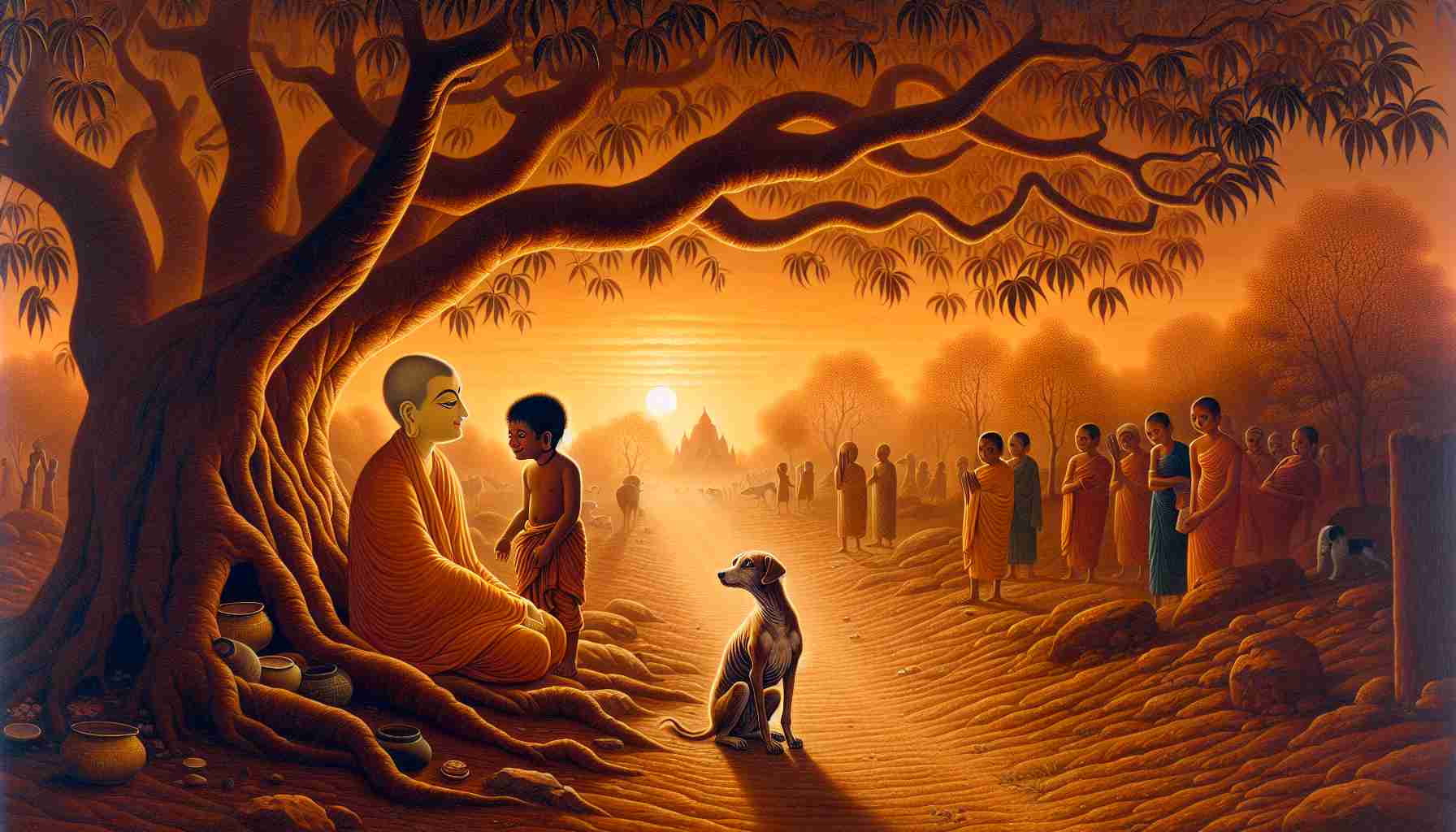

The sun hung low over the dusty road, casting long shadows from the trees above. I was just a young beggar boy then, skin taut over my bones, sleeping under bodhi leaves and eating whatever scraps kind-hearted villagers left behind. My name isn’t important—it never was. But I remember what happened the day I saw the wandering teacher, the man they called the Buddha.

Siddhartha Gautama, who would later be known as the Buddha, was born a prince in a wealthy kingdom called Kapilavatthu, in what is now southern Nepal. Though he had everything—jewels, food, fine robes—he left it all behind. Why? Because he saw suffering. And he knew deep inside that true happiness could not come from gold or power, but from wisdom. That was how he came to wander the forests and villages of India, teaching what he had discovered about life, death, and rebirth.

I had seen him before from afar—calm, barefoot, followed by monks in faded robes—but this day was different.

He had stopped at the edge of the village where I lay under a mango tree. Close by, a dog whimpered. Its bones jutted outward, and flies gathered at its eyes. No one had helped it. Many villagers believed such animals were the result of bad karma—that in another life, it may have been cruel or selfish, and now it was paying the price. They looked away, afraid and judgmental.

But the Buddha did not turn away.

He dropped to his knees beside the creature. One of his disciples, Ananda, said gently, “Master, it’s unclean. Let us move on.”

But the Buddha shook his head. “This dog suffers because of causes we do not see. Just as we once suffered because of causes we have forgotten. No being—man or animal—is without a path to liberation.”

I had never heard a man speak like that. Not about a dog. Not with such calm certainty.

The Buddha motioned to a nearby stream and asked for water. He washed the dog’s sores with care, speaking softly, like the dog could understand. Then he offered it crumbs from a bowl.

Some of the villagers gathered, whispering. “He’s wasting time,” one man said. “That animal is bound for death.”

But others grew quiet, watching him.

When the dog finally licked the crumbs and lay down peacefully, the Buddha looked up and said, “Compassion is not for those who deserve it. It is for all who suffer. If we cannot give kindness to a creature others reject, how will we treat those we fear or misunderstand?”

Years have passed, and I have long since shaved my head and taken the robes of a monk. I think of that dog often. I never knew what happened to it after that. But I knew what happened to me.

I saw that the truth the Buddha spoke wasn’t just for wise men or kings. It was for broken boys like me, and for starving dogs too.

That day, I began to understand the Dharma—not as something far away and holy, but as something as simple and as hard as kindness to all beings. That day, both the dog and I were touched by compassion.

And in that moment of shared mercy, the wheel of rebirth turned again—and something new began.