The wind was quiet that morning. I still remember how the rice leaves barely moved, like they were holding their breath. That day, I carried a heavy basket on my back—and if I’m being honest, I carried an even heavier weight in my heart.

My name is Wei, and I was only twelve years old when my father sent me to the village above the clouds. “Deliver this basket to old Master Shen,” he said. “And listen, boy—ask him for advice on your temper.”

I didn’t like that part. My anger had gotten me into trouble again—snapping at Ma, throwing my water ladle in the river because it slipped. I thought if I tried harder, trained harder, spoke louder, then everything would be right.

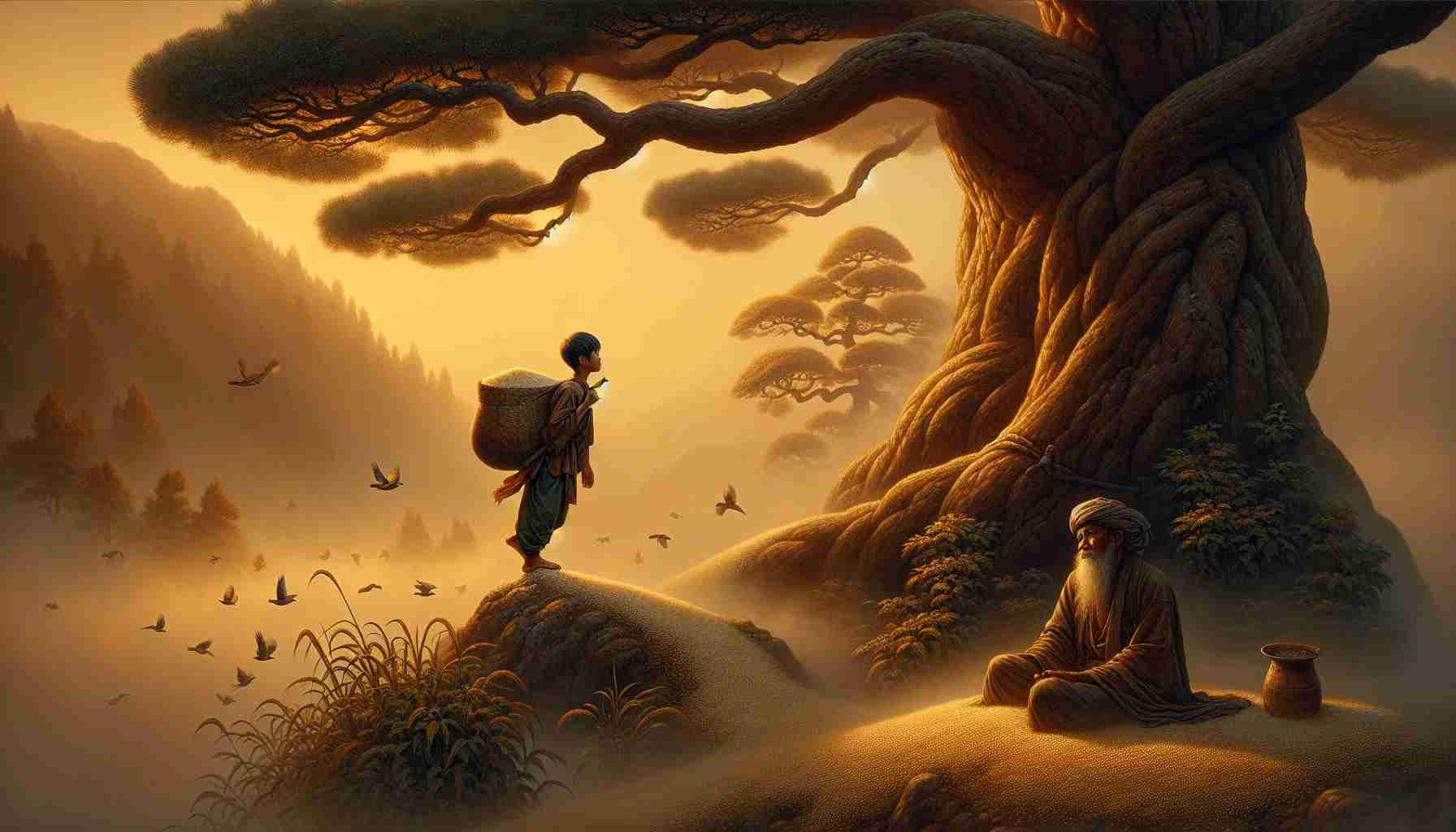

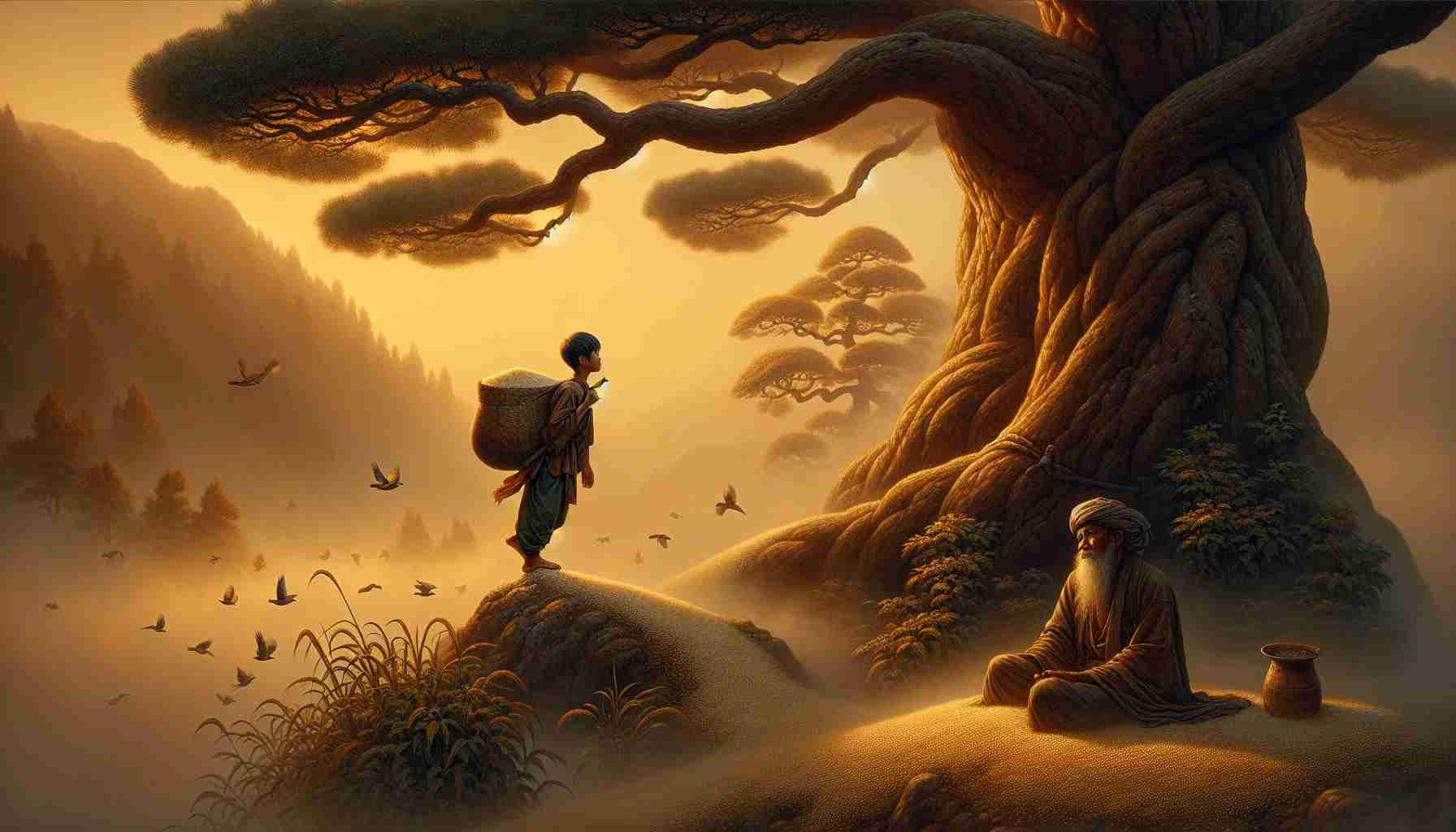

The path to the mountain village was long and steep. I grumbled the whole way up. When I reached the top, sweat running into my eyes, Master Shen was sitting under a crooked pine tree. He was very old, with more wrinkles than a dried plum and a beard that touched his knees.

“I brought your rice,” I said, dropping the basket harder than I meant to. He looked up slowly, half-smiling.

“Thank you, little cloud,” he said. “Tell me—do storms listen when you shout at them?”

I blinked. “No, sir.”

“And rivers,” he went on. “Do they flow faster because you growl at them?”

“No…” I said again, not fully understanding.

He reached into the basket and began slowly taking out handfuls of rice, letting the tiny grains slide through his fingers like sand. Some fell to the ground, and birds pecked at them.

“You are like these grains,” he said. “Always trying to go faster, louder, stronger. But look how the rice feeds the birds just by falling. It does not fight. It does not rush. And yet—it gives.”

I sat beside him, confused but curious. “But if I don’t try hard, how can I do anything important?”

Master Shen looked at me gently. “There is doing without forcing, child. That is called Wu Wei. It means flowing with life, not fighting it.”

It didn’t make much sense then. But later, as I helped him sweep his small hut, I noticed he moved slowly but finished everything with no wasted effort. He didn’t hurry. And yet, everything got done.

When it was time to go, I bowed low. “Thank you, Master Shen.”

He nodded and looked to the sky. “Remember the Tao, little cloud,” he said. “Even clouds change the world by floating.”

On the walk home, I moved more slowly. I listened to the birds. I felt the wind on my face. And when I got back, I didn’t shout at my little brother when he spilled my tea. I just laughed.

I didn’t change overnight. But now, whenever I feel the urge to push too hard, I remember the grains of rice and that old pine tree. I try to let things unfold as they are, trusting that I don’t need to fight the flow of the river.

And slowly, little by little, I’m learning the Way.

The wind was quiet that morning. I still remember how the rice leaves barely moved, like they were holding their breath. That day, I carried a heavy basket on my back—and if I’m being honest, I carried an even heavier weight in my heart.

My name is Wei, and I was only twelve years old when my father sent me to the village above the clouds. “Deliver this basket to old Master Shen,” he said. “And listen, boy—ask him for advice on your temper.”

I didn’t like that part. My anger had gotten me into trouble again—snapping at Ma, throwing my water ladle in the river because it slipped. I thought if I tried harder, trained harder, spoke louder, then everything would be right.

The path to the mountain village was long and steep. I grumbled the whole way up. When I reached the top, sweat running into my eyes, Master Shen was sitting under a crooked pine tree. He was very old, with more wrinkles than a dried plum and a beard that touched his knees.

“I brought your rice,” I said, dropping the basket harder than I meant to. He looked up slowly, half-smiling.

“Thank you, little cloud,” he said. “Tell me—do storms listen when you shout at them?”

I blinked. “No, sir.”

“And rivers,” he went on. “Do they flow faster because you growl at them?”

“No…” I said again, not fully understanding.

He reached into the basket and began slowly taking out handfuls of rice, letting the tiny grains slide through his fingers like sand. Some fell to the ground, and birds pecked at them.

“You are like these grains,” he said. “Always trying to go faster, louder, stronger. But look how the rice feeds the birds just by falling. It does not fight. It does not rush. And yet—it gives.”

I sat beside him, confused but curious. “But if I don’t try hard, how can I do anything important?”

Master Shen looked at me gently. “There is doing without forcing, child. That is called Wu Wei. It means flowing with life, not fighting it.”

It didn’t make much sense then. But later, as I helped him sweep his small hut, I noticed he moved slowly but finished everything with no wasted effort. He didn’t hurry. And yet, everything got done.

When it was time to go, I bowed low. “Thank you, Master Shen.”

He nodded and looked to the sky. “Remember the Tao, little cloud,” he said. “Even clouds change the world by floating.”

On the walk home, I moved more slowly. I listened to the birds. I felt the wind on my face. And when I got back, I didn’t shout at my little brother when he spilled my tea. I just laughed.

I didn’t change overnight. But now, whenever I feel the urge to push too hard, I remember the grains of rice and that old pine tree. I try to let things unfold as they are, trusting that I don’t need to fight the flow of the river.

And slowly, little by little, I’m learning the Way.