I was named Raghav, after Lord Rama—the ideal man from the Ramayana. But most of my life, I felt nothing like him. I was the son who lied, the husband who betrayed trust, the father who disappeared when things got difficult. My mistakes followed me, not like shadows that fade with light, but like weights I carried in my chest.

Three years ago, I left the city and moved back to my childhood village in Uttarakhand. I told people I needed peace. The truth was, I was trying to disappear. My wife had stopped calling. My daughter wouldn’t answer my messages. And I wasn’t sure I deserved their forgiveness.

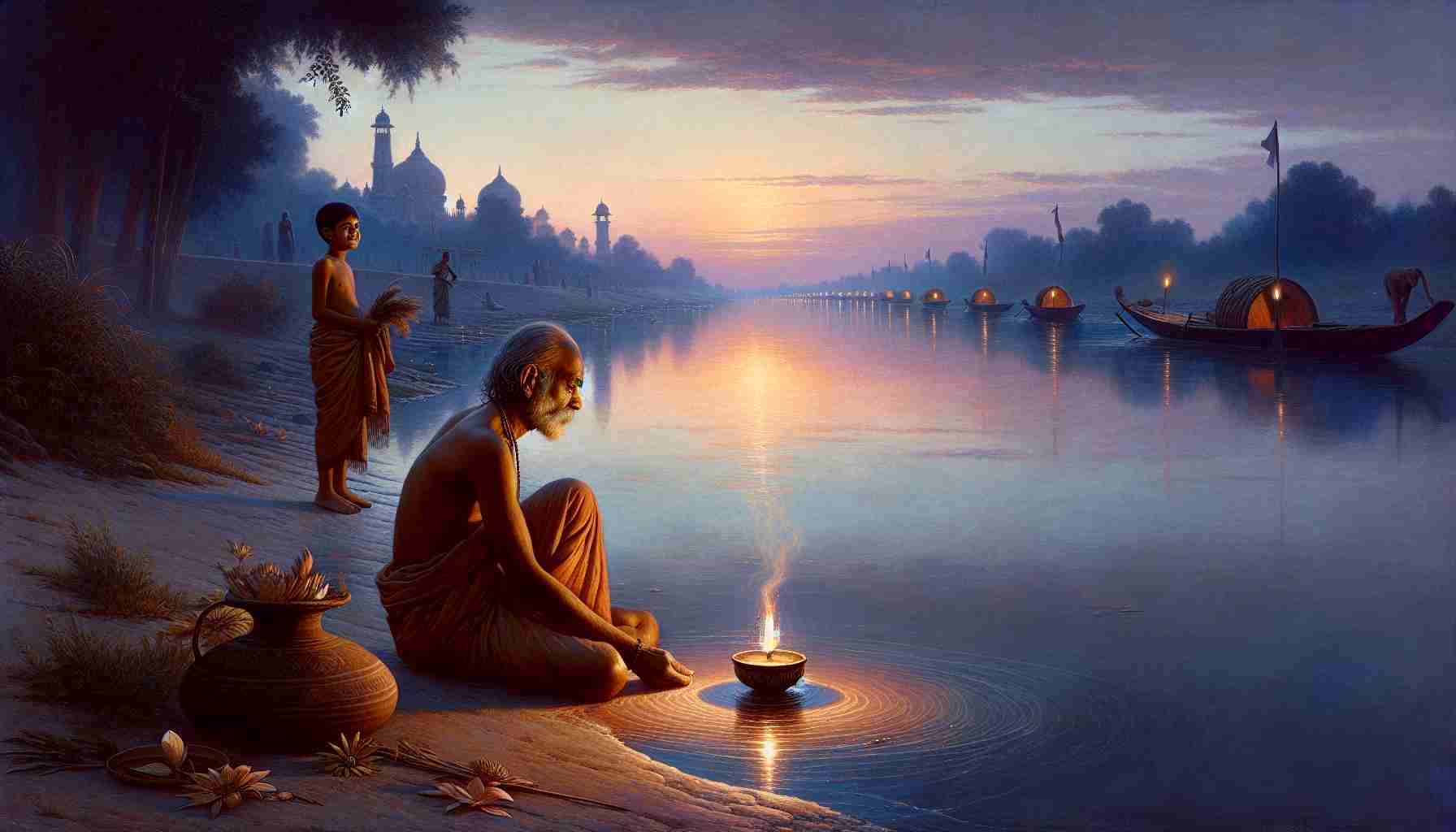

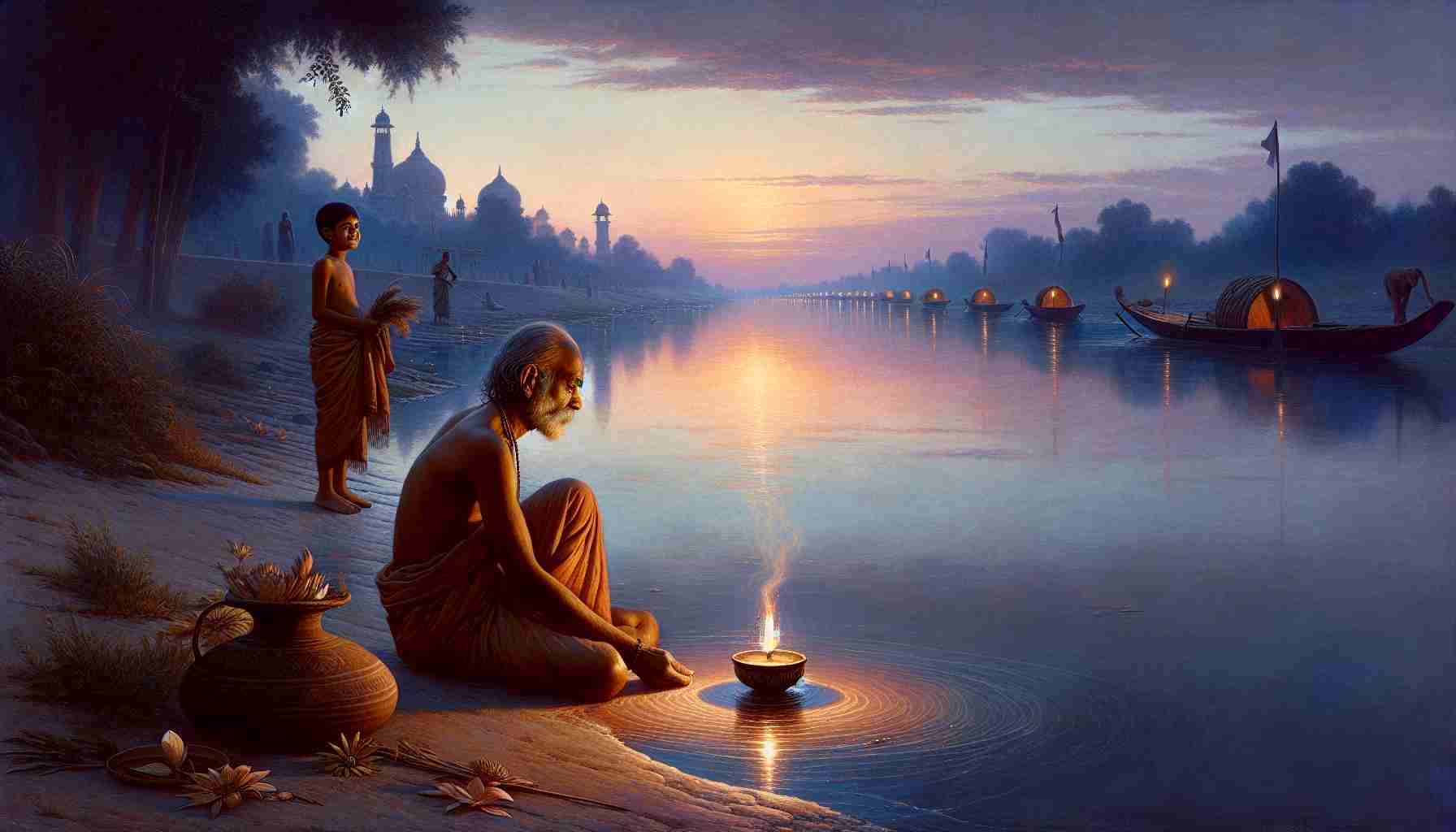

One evening, as dusk soaked the sky in orange and purple, I walked to the bank of the Ganga—the river we call Ma, Mother. I hadn’t set foot near her in two decades. Now, I felt pulled to her, as if she still remembered me.

I sat on the sand, my knees folded, and stared into the darkening water. Regret burned in my belly. I thought of the Bhagavad Gita, where Krishna tells Arjuna, “Perform your duty, abandon attachment, and be balanced in success and failure. This balance is called yoga” (BG 2.48). Balance. I had none. My actions—my karma—were full of selfishness.

A boy nearby placed a diya—a small clay oil lamp—into the river. It floated gently, the flame standing against the current. I felt something loosen inside me. I remembered how my daughter, Meera, once lit one with me during Kartik Purnima. She must have been six. She had giggled when her diya wobbled, and I had held her hand steady until it floated evenly.

I hadn’t thought of that in years.

The boy turned to me and smiled. “Do you want to light one, uncle?”

I blinked. “Yes,” I whispered.

He gave me a diya already prepared, and I held it between my palms. I didn’t pray for forgiveness. I just whispered Meera’s name.

As I let the diya go, tears came. Not the heavy kind born of shame, but the simple kind that come when something starts to heal.

In the Chandogya Upanishad, it says, “As one acts, so does he become.” And so, I chose to act.

The next day, I made a call. Meera didn’t pick up, but I left a message. I didn’t explain everything. I just told her I was sorry, that I remembered Kartik by the river, and that I hope her light is still strong.

Every morning now, I rise before the sun and help sweep the temple steps. It’s not much. But it’s action, even in small form—karma moving toward a better path.

In the Mahabharata, Yudhishthira says, “A man becomes pure through pure actions.” And for the first time in a long while, I believe purity is possible.

Maybe healing doesn’t begin with being healed.

Maybe it begins the moment we stop running.

I was named Raghav, after Lord Rama—the ideal man from the Ramayana. But most of my life, I felt nothing like him. I was the son who lied, the husband who betrayed trust, the father who disappeared when things got difficult. My mistakes followed me, not like shadows that fade with light, but like weights I carried in my chest.

Three years ago, I left the city and moved back to my childhood village in Uttarakhand. I told people I needed peace. The truth was, I was trying to disappear. My wife had stopped calling. My daughter wouldn’t answer my messages. And I wasn’t sure I deserved their forgiveness.

One evening, as dusk soaked the sky in orange and purple, I walked to the bank of the Ganga—the river we call Ma, Mother. I hadn’t set foot near her in two decades. Now, I felt pulled to her, as if she still remembered me.

I sat on the sand, my knees folded, and stared into the darkening water. Regret burned in my belly. I thought of the Bhagavad Gita, where Krishna tells Arjuna, “Perform your duty, abandon attachment, and be balanced in success and failure. This balance is called yoga” (BG 2.48). Balance. I had none. My actions—my karma—were full of selfishness.

A boy nearby placed a diya—a small clay oil lamp—into the river. It floated gently, the flame standing against the current. I felt something loosen inside me. I remembered how my daughter, Meera, once lit one with me during Kartik Purnima. She must have been six. She had giggled when her diya wobbled, and I had held her hand steady until it floated evenly.

I hadn’t thought of that in years.

The boy turned to me and smiled. “Do you want to light one, uncle?”

I blinked. “Yes,” I whispered.

He gave me a diya already prepared, and I held it between my palms. I didn’t pray for forgiveness. I just whispered Meera’s name.

As I let the diya go, tears came. Not the heavy kind born of shame, but the simple kind that come when something starts to heal.

In the Chandogya Upanishad, it says, “As one acts, so does he become.” And so, I chose to act.

The next day, I made a call. Meera didn’t pick up, but I left a message. I didn’t explain everything. I just told her I was sorry, that I remembered Kartik by the river, and that I hope her light is still strong.

Every morning now, I rise before the sun and help sweep the temple steps. It’s not much. But it’s action, even in small form—karma moving toward a better path.

In the Mahabharata, Yudhishthira says, “A man becomes pure through pure actions.” And for the first time in a long while, I believe purity is possible.

Maybe healing doesn’t begin with being healed.

Maybe it begins the moment we stop running.