I was just a servant boy, barely twelve, sweeping the monastery courtyard when the air changed that day. My name is Danu, and though my hands have known little more than brooms and rice pots, I carry a memory of a moment that taught me the depth of real compassion.

We lived in Kosambi, a bustling city in ancient India. It was a place of fragrant markets, loud debates, and quiet monks. The great Teacher—Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha—had come to stay in our monastery for the rains retreat. Even as a child, I could sense something different about him. His presence calmed even the loudest birds and softened the footsteps of angry men.

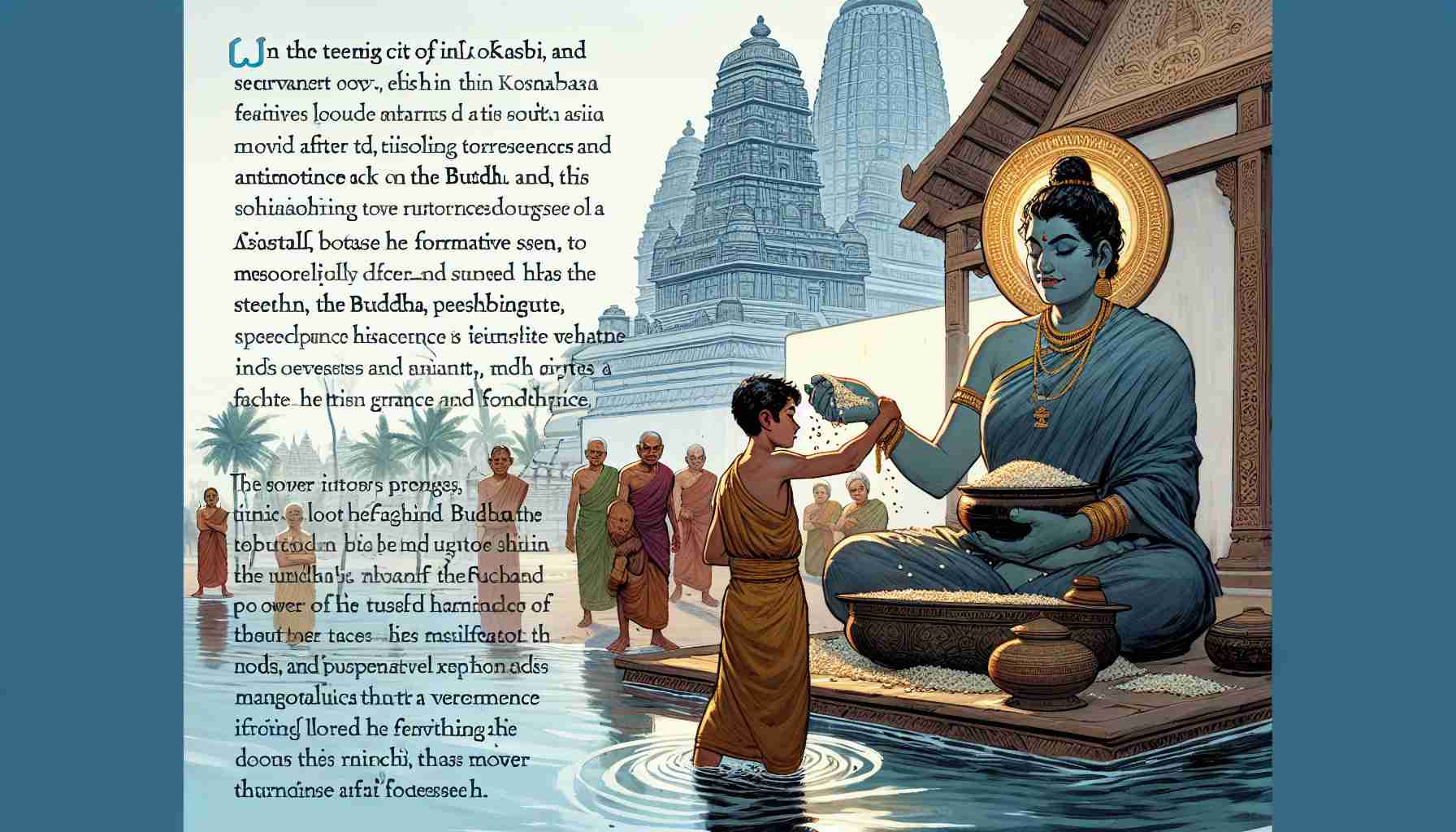

Word spread like fire through the kitchens: a wealthy woman named Sundarī had invited the Buddha and his disciples to her home. She was known for both her generosity and her pride. Some said she offered gifts to gain honor, not from her heart, and others whispered of jealousy toward the peace the monks carried with them.

That morning, I watched as Venerable Maha Moggallāna, one of the Buddha’s foremost disciples known for his spiritual powers and loyalty, prepared with the others for the journey. His eyes were sharp like a hawk, but kind. He had once been a prince, choosing the monk’s robe over a life of gold and ease. I admired him deeply.

What no one—except the sharp-eyed Moggallāna—could have known was that Sundarī had prepared poisoned rice for the Buddha. Her heart, poisoned by envy, sought to harm the one who caused her own unrest. She had grown frustrated that her offerings—given with an eager eye for praise—had brought her no inner peace.

As the monks arrived, Sundarī greeted them with practiced grace, presenting the rice on fine silver trays. But Moggallāna, sensing danger with his refined mindfulness, intercepted the tray meant for the Enlightened One.

He ate it himself.

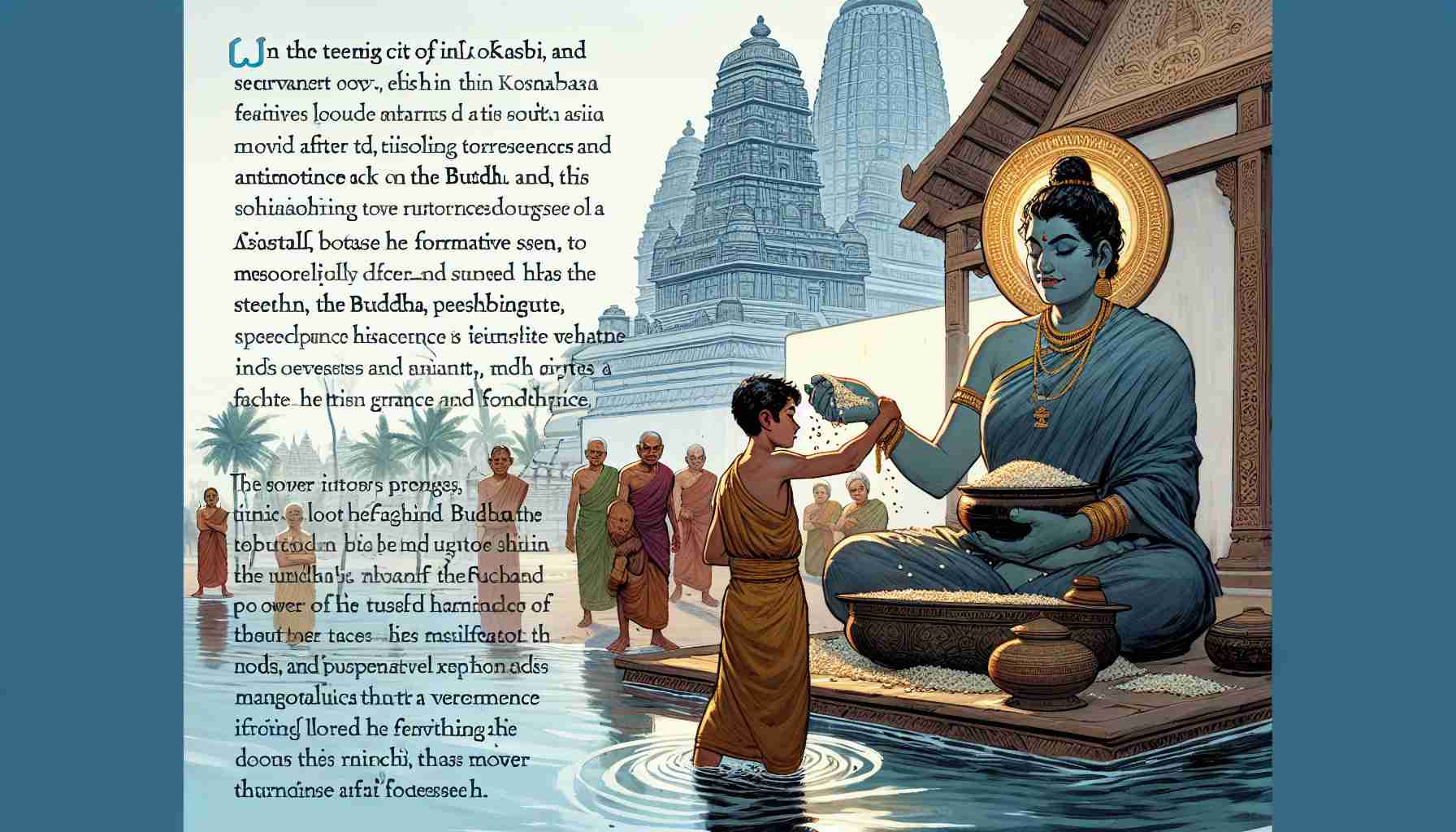

The silence that followed was like thick fog. I watched from the hedge, hidden but trembling. The other monks held their breath as Moggallāna, pale but composed, stood still and then bowed. The poison had touched his body—but not his mind.

He turned to Sundarī and said gently, “Hatred cannot be overcome by hatred. Only by love is hatred overcome. This is the eternal law.”

Sundarī dropped to her knees, tears soaking into the earth. Her hands, once poised with pride, now trembled with shame. She had tried to harm one who had never wronged her—one who had only tried to teach peace.

“I have failed,” she whispered.

Moggallāna did not scold her. Instead, with great peace, he said, “You have not failed if you choose now to change. Let go. Begin again.”

That day, I saw what it meant to truly let go. Not just of riches or offerings—but of anger, pride, and ego. I still recall the quiet way Moggallāna smiled, never once angry at her attempt.

What Sundarī realized that day, and what I carry still, is this: even poisoned rice, met with mindfulness and compassion, can become the turning point of a pure heart.

And I understood then—true strength is not in power, but in deep, humble love.

I gathered my broom, and as I swept the courtyard after they left, I no longer dreamed of kings or warriors.

I wanted to walk the path of peace.

I was just a servant boy, barely twelve, sweeping the monastery courtyard when the air changed that day. My name is Danu, and though my hands have known little more than brooms and rice pots, I carry a memory of a moment that taught me the depth of real compassion.

We lived in Kosambi, a bustling city in ancient India. It was a place of fragrant markets, loud debates, and quiet monks. The great Teacher—Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha—had come to stay in our monastery for the rains retreat. Even as a child, I could sense something different about him. His presence calmed even the loudest birds and softened the footsteps of angry men.

Word spread like fire through the kitchens: a wealthy woman named Sundarī had invited the Buddha and his disciples to her home. She was known for both her generosity and her pride. Some said she offered gifts to gain honor, not from her heart, and others whispered of jealousy toward the peace the monks carried with them.

That morning, I watched as Venerable Maha Moggallāna, one of the Buddha’s foremost disciples known for his spiritual powers and loyalty, prepared with the others for the journey. His eyes were sharp like a hawk, but kind. He had once been a prince, choosing the monk’s robe over a life of gold and ease. I admired him deeply.

What no one—except the sharp-eyed Moggallāna—could have known was that Sundarī had prepared poisoned rice for the Buddha. Her heart, poisoned by envy, sought to harm the one who caused her own unrest. She had grown frustrated that her offerings—given with an eager eye for praise—had brought her no inner peace.

As the monks arrived, Sundarī greeted them with practiced grace, presenting the rice on fine silver trays. But Moggallāna, sensing danger with his refined mindfulness, intercepted the tray meant for the Enlightened One.

He ate it himself.

The silence that followed was like thick fog. I watched from the hedge, hidden but trembling. The other monks held their breath as Moggallāna, pale but composed, stood still and then bowed. The poison had touched his body—but not his mind.

He turned to Sundarī and said gently, “Hatred cannot be overcome by hatred. Only by love is hatred overcome. This is the eternal law.”

Sundarī dropped to her knees, tears soaking into the earth. Her hands, once poised with pride, now trembled with shame. She had tried to harm one who had never wronged her—one who had only tried to teach peace.

“I have failed,” she whispered.

Moggallāna did not scold her. Instead, with great peace, he said, “You have not failed if you choose now to change. Let go. Begin again.”

That day, I saw what it meant to truly let go. Not just of riches or offerings—but of anger, pride, and ego. I still recall the quiet way Moggallāna smiled, never once angry at her attempt.

What Sundarī realized that day, and what I carry still, is this: even poisoned rice, met with mindfulness and compassion, can become the turning point of a pure heart.

And I understood then—true strength is not in power, but in deep, humble love.

I gathered my broom, and as I swept the courtyard after they left, I no longer dreamed of kings or warriors.

I wanted to walk the path of peace.