I was once a man who turned away from dharma — the path of righteousness.

My name is Rajan. I was born in a small village near the banks of the Yamuna River. My father was a priest who offered daily prayers to Vishnu, the protector of the universe, in our temple. I, however, walked a different path. In my youth, I chased profit, ignored tradition, and spoke harshly to those who reminded me of my roots. I moved to the city, built a business, and when it failed, I returned home thirty years later with empty pockets and a heart full of shame.

My father had passed. The old temple stood silent. Stones cracked, kann facing algae. I had not even come for his shraddha — the last rites. That guilt burned more than any loss.

One morning, as the monsoon clouds swirled, I walked to the Yamuna and sat beside the water. Watching the river, I remembered a verse my father used to chant from the Bhagavad Gita — “Even if you were the most sinful of sinners, you can cross beyond all sin through the boat of sacred knowledge” (Gita 4.36). I scoffed at it once. But that day, it stayed with me.

I didn’t know how to fix what I had broken. My mind wandered to the Ramayana — how even after Ravana had ruined all, Vibhishana, his brother, still sought refuge in Rama, the great king and incarnation of the Divine. Rama accepted him. That gave me a small hope: maybe sacred action wasn't about erasing the past, but changing its direction.

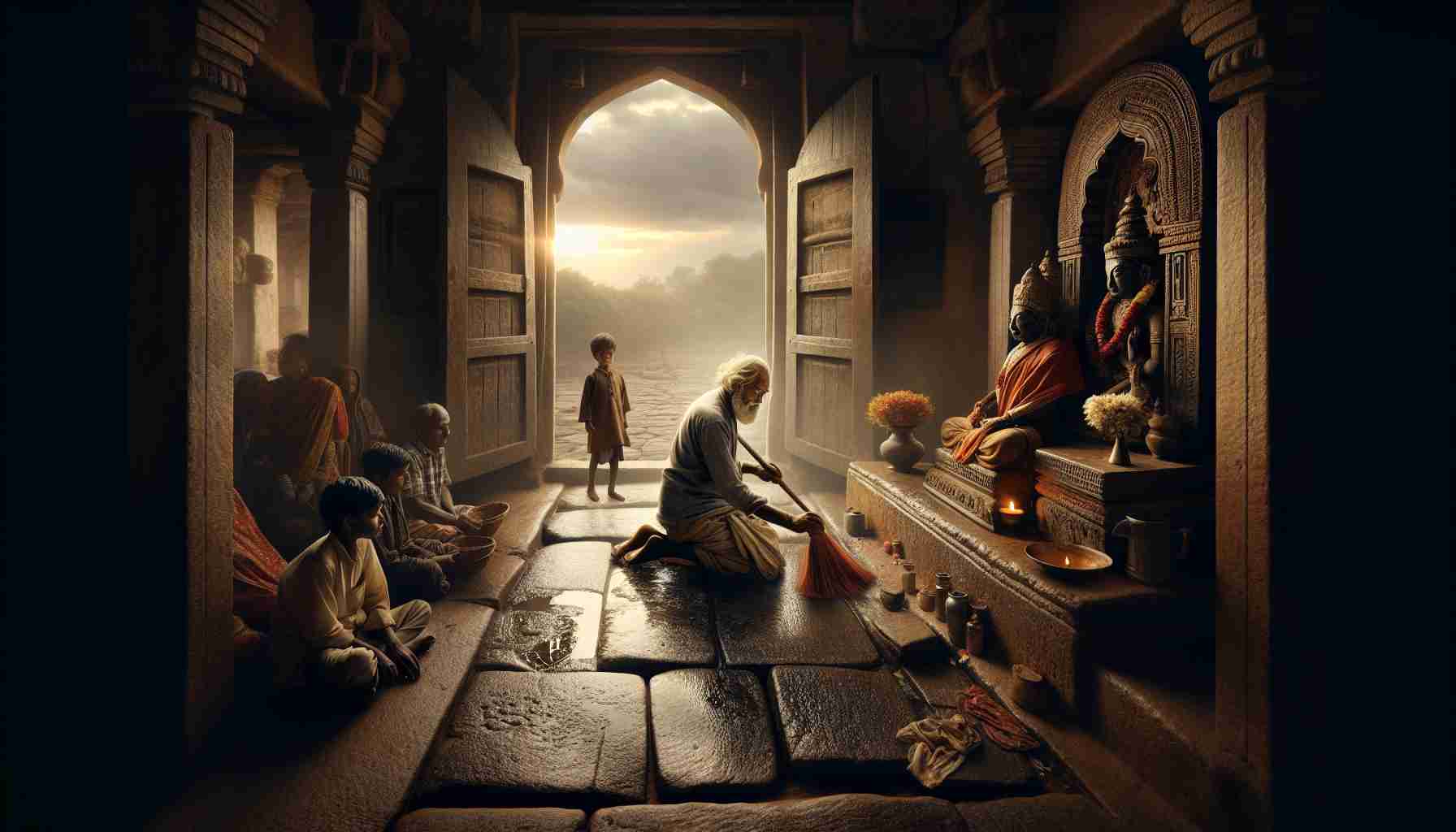

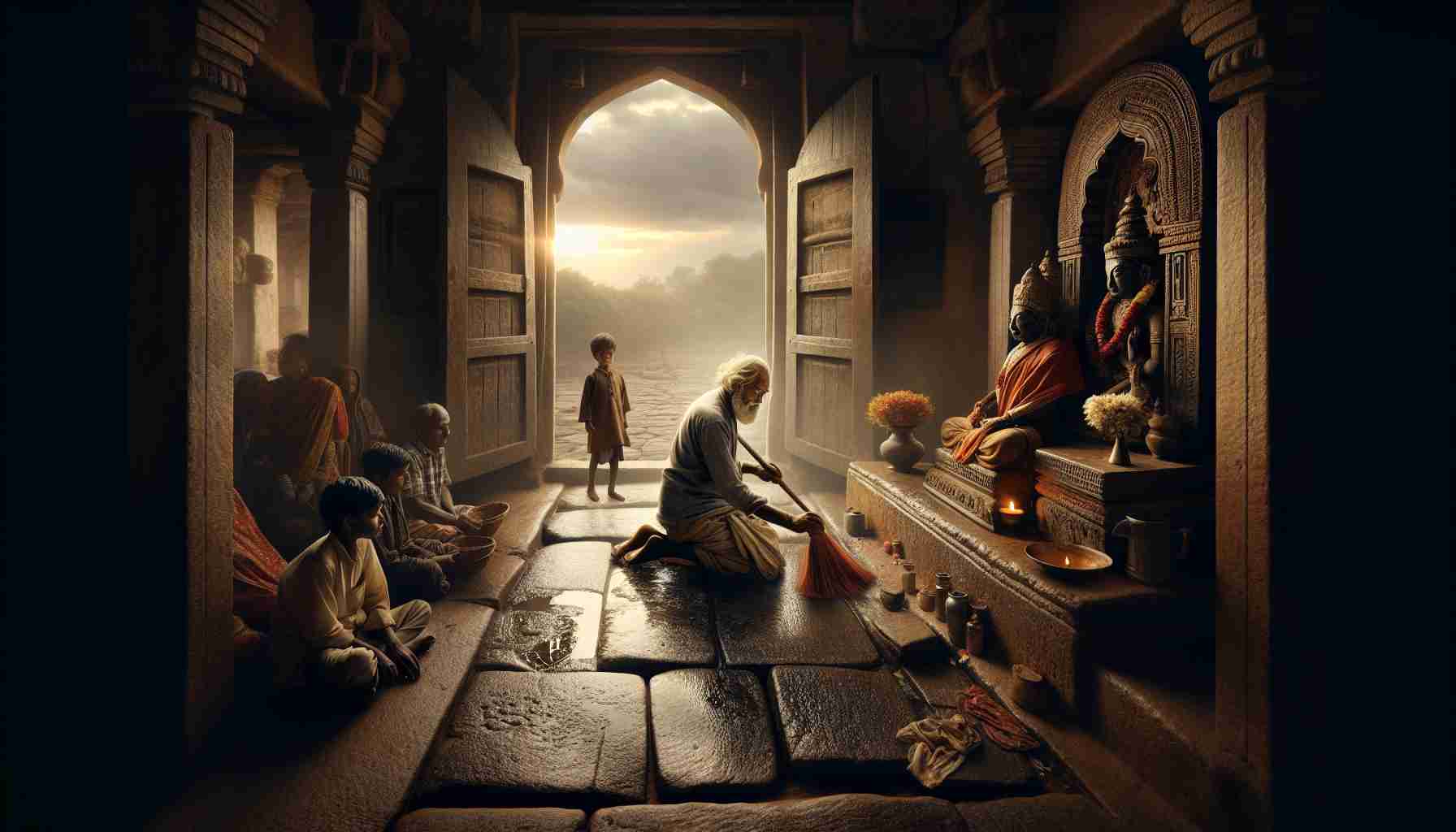

So I began to clean the temple.

Brick by brick, I lifted the dust, walked barefoot across the cold floors, and scrubbed the altars where no man had prayed in years. Some villagers watched. Some nodded. A few joined.

Each morning, I lit a diya — a small oil lamp — before the Vishnu murti, whispering apologies I didn’t know how to say aloud. One day, I found an old boy, about ten, sitting quietly as I swept. He offered to help.

“Why do you come?” I asked him.

He shrugged. “You love this place. I want to see why.”

That broke something in me — gently, like rain soaking cracked earth.

I began reciting simple verses again. Sankats get lighter when spoken with devotion. One morning, my voice wavered when I spoke from the Isha Upanishad: “Only by doing selfless actions may one hope to live a hundred years” (Isa 2). I was already past sixty. But for the first time, my days had meaning, not regret.

I do not claim redemption as something I earned. But I do believe what Krishna promises in the Gita is true — “Abandon all duties and surrender to Me. I will deliver you from all sin; do not fear” (Gita 18.66).

I surrendered by returning. By serving. By daring to hope that my sankalpa — sacred intention — counted for something.

Now, when I sit under the peepal tree behind the temple, with children laughing and elders sitting in morning sun, I feel the presence of the Divine not in what I fixed — but in how I was forgiven.

Quietly. Through sacred action.

I was once a man who turned away from dharma — the path of righteousness.

My name is Rajan. I was born in a small village near the banks of the Yamuna River. My father was a priest who offered daily prayers to Vishnu, the protector of the universe, in our temple. I, however, walked a different path. In my youth, I chased profit, ignored tradition, and spoke harshly to those who reminded me of my roots. I moved to the city, built a business, and when it failed, I returned home thirty years later with empty pockets and a heart full of shame.

My father had passed. The old temple stood silent. Stones cracked, kann facing algae. I had not even come for his shraddha — the last rites. That guilt burned more than any loss.

One morning, as the monsoon clouds swirled, I walked to the Yamuna and sat beside the water. Watching the river, I remembered a verse my father used to chant from the Bhagavad Gita — “Even if you were the most sinful of sinners, you can cross beyond all sin through the boat of sacred knowledge” (Gita 4.36). I scoffed at it once. But that day, it stayed with me.

I didn’t know how to fix what I had broken. My mind wandered to the Ramayana — how even after Ravana had ruined all, Vibhishana, his brother, still sought refuge in Rama, the great king and incarnation of the Divine. Rama accepted him. That gave me a small hope: maybe sacred action wasn't about erasing the past, but changing its direction.

So I began to clean the temple.

Brick by brick, I lifted the dust, walked barefoot across the cold floors, and scrubbed the altars where no man had prayed in years. Some villagers watched. Some nodded. A few joined.

Each morning, I lit a diya — a small oil lamp — before the Vishnu murti, whispering apologies I didn’t know how to say aloud. One day, I found an old boy, about ten, sitting quietly as I swept. He offered to help.

“Why do you come?” I asked him.

He shrugged. “You love this place. I want to see why.”

That broke something in me — gently, like rain soaking cracked earth.

I began reciting simple verses again. Sankats get lighter when spoken with devotion. One morning, my voice wavered when I spoke from the Isha Upanishad: “Only by doing selfless actions may one hope to live a hundred years” (Isa 2). I was already past sixty. But for the first time, my days had meaning, not regret.

I do not claim redemption as something I earned. But I do believe what Krishna promises in the Gita is true — “Abandon all duties and surrender to Me. I will deliver you from all sin; do not fear” (Gita 18.66).

I surrendered by returning. By serving. By daring to hope that my sankalpa — sacred intention — counted for something.

Now, when I sit under the peepal tree behind the temple, with children laughing and elders sitting in morning sun, I feel the presence of the Divine not in what I fixed — but in how I was forgiven.

Quietly. Through sacred action.