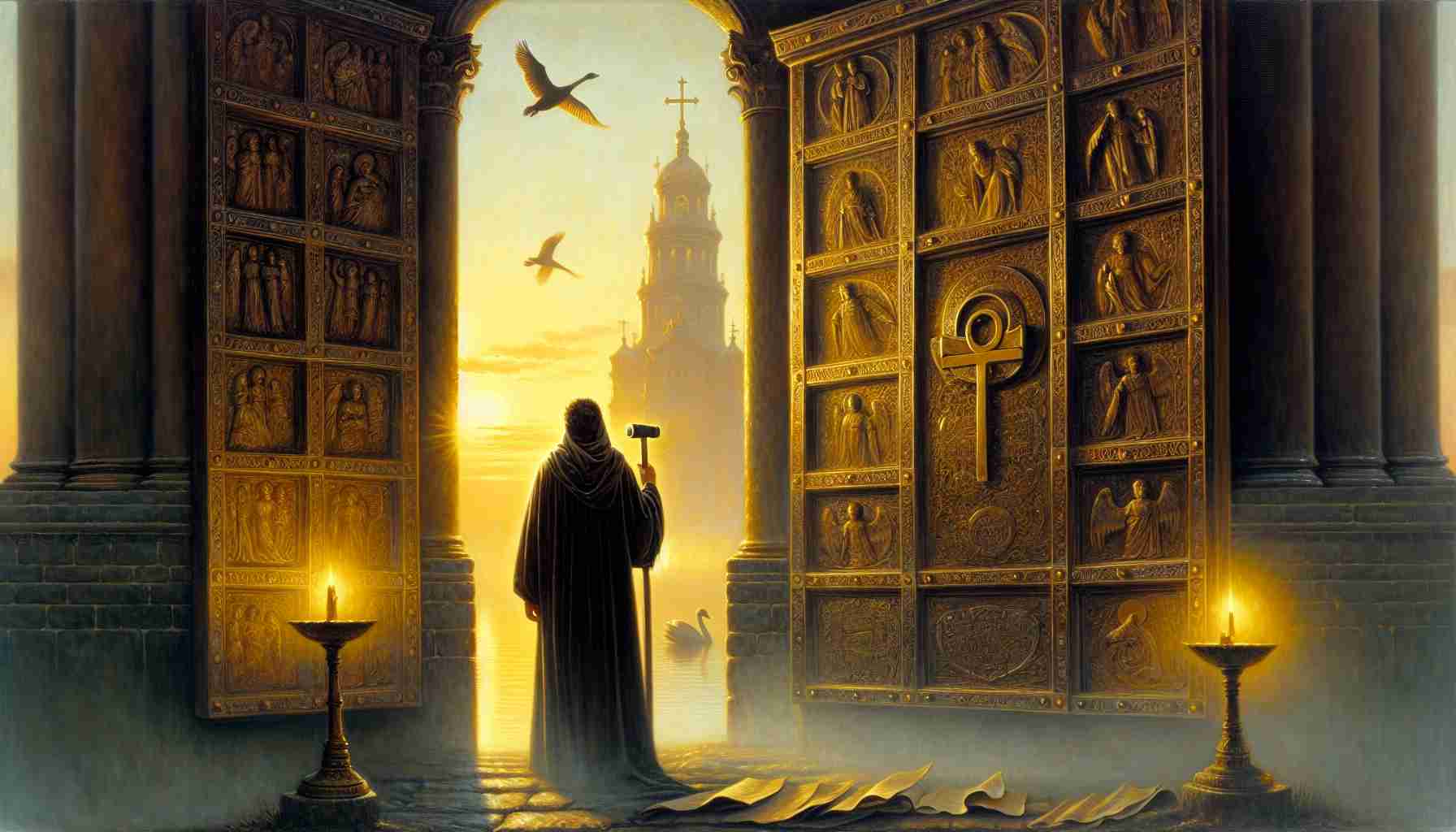

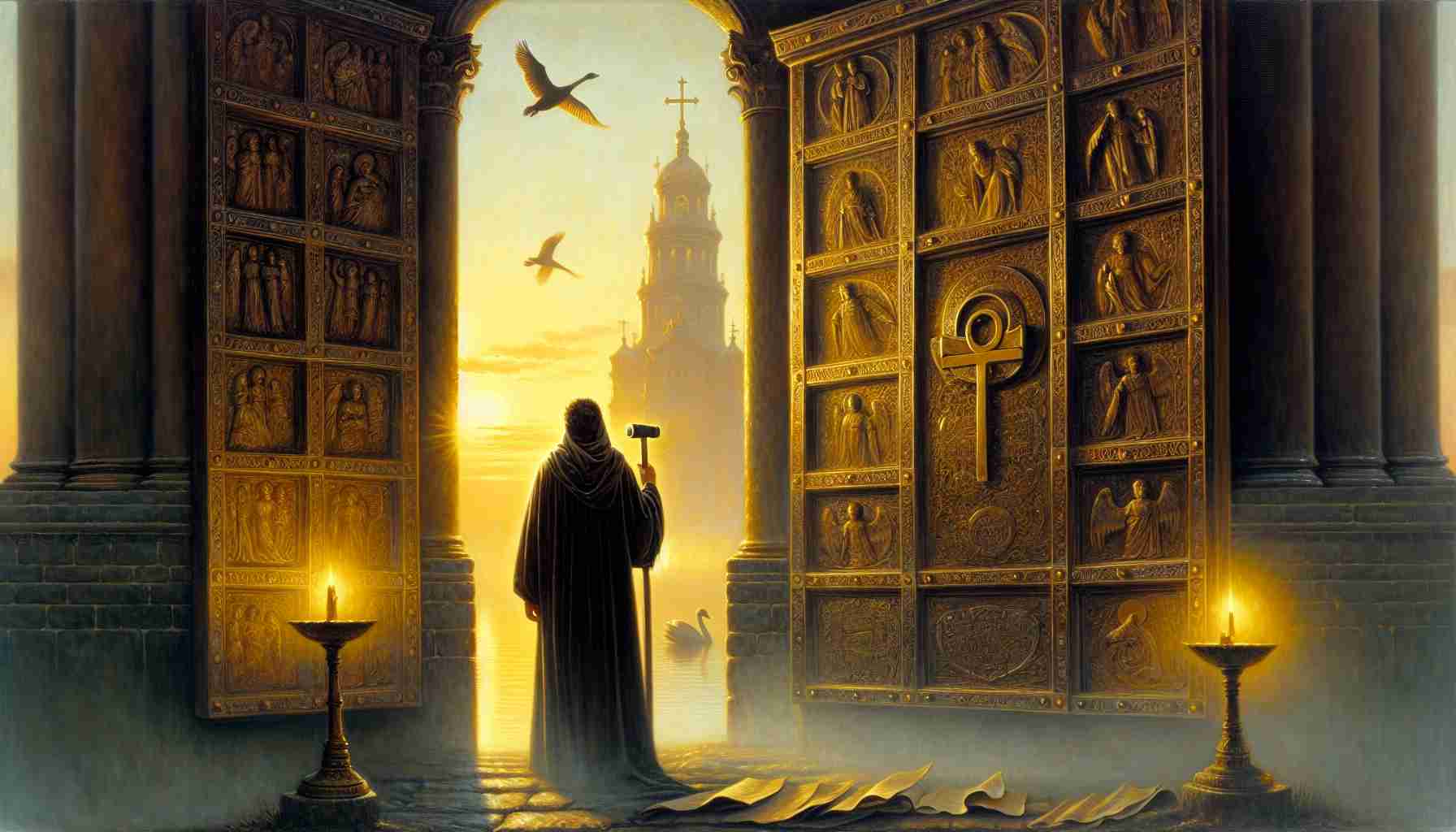

Mist rolled low across the cobblestones of Wittenberg, darting between the ankles of cloaked market-goers and curling upward along the wooden doors of Schlosskirche—the Castle Church. Dawn had not yet crested over the Elbe River, and the hush of All Saints’ Day morning cloaked the town as solemnly as the cold.

The hammer struck once, sharp and final.

The sound echoed off the nave’s stone buttresses, a cry not unlike thunder before a storm. A monk in a black Augustinian robe stood before the church’s massive twin doors, clutching a parchment already pinned in four corners with iron studs. His fingers trembled only slightly as he pressed one final nail deep into the grain.

Doctor Martin Luther stepped back and stared at his work lit by flickering torches. His face bore no pride, only grave determination—as though he’d written a letter not to the Pope, but to time itself.

Above him loomed the great west doors of the Castle Church, once carved from sturdy oak, now overlaid with bronze and sanctified by tradition. Every All Saints’ Day for a hundred years, pilgrims had gathered here to honor the sacred relics housed within, each one offering precious time off Purgatory in exchange for a glimpse or a coin.

Inside, 1,905 relics—bones of saints, thorns said to crown the Christ, hairs from the Virgin Mary—sat under gleaming glass, guarded by the Electors of Saxony. Indulgences marked by papal bulls could be bought only steps away.

It was to this stronghold of unquestioned authority that Luther had nailed his ninety-five challenges.

And though the act seemed a spark small enough to be snuffed by the morning crowd, it found fuel in the discontent of many. The document was written in Latin for debate among scholars, but word crept past monastery walls, stretching along the roads between Wittenberg and Rome, kindling whispers in candlelit taverns and echoing through vaulted cathedrals.

None who passed the church that day knew yet what holy tremors had been birthed.

In the days that followed, townsfolk lingered by the door. Some knelt. Some spat. A few scribes copied the theses by hand, taking them to printers who smelled of ink and ambition. The Latin gave way to German, and soon the parchment traveled faster than bishops could warn. In Mainz, in Nuremberg, in Strasbourg, the words sparked debate—and fear.

Inside the church, the relics waited in their gilded cases. But fewer pilgrims came now, uncertain whether their journey had grown into sin.

The doors themselves, centuries old, became silent witnesses to wrath and hope. In 1760, fire swallowed their timber during the Seven Years’ War. But the memory of what had been nailed there had already become legend. In 1858, King Frederick William IV of Prussia ordered new doors cast with Luther’s full Latin theses, bronze replacing wood, permanence enshrining protest. They stood ten feet tall, adorned in Gothic tracery, defying time and tide.

Yet not all agreed on what Luther intended.

Some whispered that he had never intended to spark reformation but had hoped for reasoned dialogue. Others insisted he had never actually nailed the document at all, but sent it by letter to Archbishop Albert of Mainz. The nailing, they argued, was a romantic invention by Philipp Melanchthon years later—uncertain, unprovable.

Still, the church stood.

The very stones bore witness to centuries of turning faith, from Catholic grandeur to Lutheran simplicity; from medieval sanctity to Enlightenment scrutiny; from Nazi desecration to reunified reverence. And through wars, sermons, and snow, people kept coming.

In 1517, Luther had walked to the door with trembling hands. He questioned whether salvation could be sold. The Gospels had spoken—the just shall live by faith (Romans 1:17)—not coins. Christ overturned tables in the temple, not to raise funds, but to cleanse worship. So too did Luther seek a cleansing, not a war.

But wars came nonetheless.

Through turmoil, the church of Wittenberg bore more than relics—it bore the weight of conscience. The hammer’s echo outlasted empires, shaking off centuries of dogma. To some, it wounded unity. To others, it resurrected truth.

Centuries later, in reverent silence, visitors still stand before the great bronze doors. They gaze up at the Latin words, many unreadable to them, yet heavy with the echo of a man’s conviction.

The church bells toll on Reformation Day, and chants rise in tones old and new—praising not relics, but grace. A monk once hammered his doubts to a door of power. But it was not doubt that changed the world.

It was faith, nailed to history.

Mist rolled low across the cobblestones of Wittenberg, darting between the ankles of cloaked market-goers and curling upward along the wooden doors of Schlosskirche—the Castle Church. Dawn had not yet crested over the Elbe River, and the hush of All Saints’ Day morning cloaked the town as solemnly as the cold.

The hammer struck once, sharp and final.

The sound echoed off the nave’s stone buttresses, a cry not unlike thunder before a storm. A monk in a black Augustinian robe stood before the church’s massive twin doors, clutching a parchment already pinned in four corners with iron studs. His fingers trembled only slightly as he pressed one final nail deep into the grain.

Doctor Martin Luther stepped back and stared at his work lit by flickering torches. His face bore no pride, only grave determination—as though he’d written a letter not to the Pope, but to time itself.

Above him loomed the great west doors of the Castle Church, once carved from sturdy oak, now overlaid with bronze and sanctified by tradition. Every All Saints’ Day for a hundred years, pilgrims had gathered here to honor the sacred relics housed within, each one offering precious time off Purgatory in exchange for a glimpse or a coin.

Inside, 1,905 relics—bones of saints, thorns said to crown the Christ, hairs from the Virgin Mary—sat under gleaming glass, guarded by the Electors of Saxony. Indulgences marked by papal bulls could be bought only steps away.

It was to this stronghold of unquestioned authority that Luther had nailed his ninety-five challenges.

And though the act seemed a spark small enough to be snuffed by the morning crowd, it found fuel in the discontent of many. The document was written in Latin for debate among scholars, but word crept past monastery walls, stretching along the roads between Wittenberg and Rome, kindling whispers in candlelit taverns and echoing through vaulted cathedrals.

None who passed the church that day knew yet what holy tremors had been birthed.

In the days that followed, townsfolk lingered by the door. Some knelt. Some spat. A few scribes copied the theses by hand, taking them to printers who smelled of ink and ambition. The Latin gave way to German, and soon the parchment traveled faster than bishops could warn. In Mainz, in Nuremberg, in Strasbourg, the words sparked debate—and fear.

Inside the church, the relics waited in their gilded cases. But fewer pilgrims came now, uncertain whether their journey had grown into sin.

The doors themselves, centuries old, became silent witnesses to wrath and hope. In 1760, fire swallowed their timber during the Seven Years’ War. But the memory of what had been nailed there had already become legend. In 1858, King Frederick William IV of Prussia ordered new doors cast with Luther’s full Latin theses, bronze replacing wood, permanence enshrining protest. They stood ten feet tall, adorned in Gothic tracery, defying time and tide.

Yet not all agreed on what Luther intended.

Some whispered that he had never intended to spark reformation but had hoped for reasoned dialogue. Others insisted he had never actually nailed the document at all, but sent it by letter to Archbishop Albert of Mainz. The nailing, they argued, was a romantic invention by Philipp Melanchthon years later—uncertain, unprovable.

Still, the church stood.

The very stones bore witness to centuries of turning faith, from Catholic grandeur to Lutheran simplicity; from medieval sanctity to Enlightenment scrutiny; from Nazi desecration to reunified reverence. And through wars, sermons, and snow, people kept coming.

In 1517, Luther had walked to the door with trembling hands. He questioned whether salvation could be sold. The Gospels had spoken—the just shall live by faith (Romans 1:17)—not coins. Christ overturned tables in the temple, not to raise funds, but to cleanse worship. So too did Luther seek a cleansing, not a war.

But wars came nonetheless.

Through turmoil, the church of Wittenberg bore more than relics—it bore the weight of conscience. The hammer’s echo outlasted empires, shaking off centuries of dogma. To some, it wounded unity. To others, it resurrected truth.

Centuries later, in reverent silence, visitors still stand before the great bronze doors. They gaze up at the Latin words, many unreadable to them, yet heavy with the echo of a man’s conviction.

The church bells toll on Reformation Day, and chants rise in tones old and new—praising not relics, but grace. A monk once hammered his doubts to a door of power. But it was not doubt that changed the world.

It was faith, nailed to history.